Folders |

Nothing Good Is Ever Easy - Inside Abdul Alzindani's 1995 Foot Locker ChampionshipPublished by

‘Nothing Good is Ever Easy’Abdul Alzindani Looks Back 25 Years After Foot Locker TriumphA DyeStat story by Dave Devine

The tree, at least, felt sturdy. A solid thing. Reliable. Capable of supporting him. Fresh off his warm-up jog for the 1995 Foot Locker Cross Country Championships, Abdul Alzindani needed something sturdy. Something more stable than his own withering confidence. A short distance from the gathering crowd in San Diego’s Balboa Park, he found a stand of towering Eucalyptus trees, sank to the ground against a trunk, and began to cry. The tears were for — what? He wasn’t sure. For the sudden doubt coursing through him. For the uncertainty. For the sense that his body, so reliable this entire cross country season, was about to betray him at the biggest moment. That the side-stitch he’d suffered two weeks earlier at the Foot Locker Midwest Regional in Kenosha, Wisconsin, the one that blemished an unbeaten senior year and nearly cost him a berth in this national meet, was flaring up again. He’d spent the two weeks between the regional race and the national final with an icepack pressed against his abdomen, shuffling between classes at Fordson High in Dearborn, Michigan, hoping for the best. Figuring things would be better in San Diego. The warm-up jog had been, as it is for many runners before a race, a kind of diagnostic test. How will the body feel? How will the legs respond? And, perhaps most pertinent in Abdul’s case, how will any lingering aches or injuries react? Head against that tree, Abdul had his answer. The pain below his ribs was still there. He’d placed 22nd in this race a year earlier, charging coltishly to the lead through the first mile before fading hard off his ambitious pace. This was supposed to be his redemption race. He’d waited 365 days for it to come. Spent an entire year putting in the miles. Attending to the small things. All the stretching and striders and recovery. A full year of closing his eyes each night before bed and running this race in his head. Imagining the turns, the hills, the way he’d charge home in the final straight. Opening his eyes, just before flicking off his lights, to stare at a simple message he’d printed out and taped to his ceiling: “Nothing good is ever easy, and nothing easy is ever good.” It was the last thing he saw each night, the first thing he read each morning. One year of hard work and focus, only to end up back here at Balboa, slumped against a tree, sobbing. What if the pain in his side robbed him of breath, the way it did in Kenosha? What if he got skittish again? Impatient? What if this was Sharif Karie’s year, the way people had been saying? What if the kid from Somalia, now running for West Springfield, Virginia, couldn’t be stopped? What if his kick was as potent as everyone believed? What if, what if, what if… But also: What if this year belonged to him — Abdul’s year — the way he’d believed all along? He knew he was fitter than he’d ever been. Knew, with certainty, he could win. Against that tree, Abdul mulled these contradictory things. The confidence and doubt. Fear and hope. Wondering if he could hold these conflicting realities together long enough to win this race. If he could allow each the space it needed, without all of it consuming him.

Childhood was like that, too, full of contradictions. Especially in a place like Yemen, where Abdul Alzindani grew up. Located at the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, bordering Saudi Arabia and Oman, Yemen has long been desperately poor; a nation that has endured decades of internal conflict and a seemingly endless cycle of civil war. When Alzindani thinks back on his childhood there, he pulls forward memories of beauty and joy, laughter and light, muddled by the persistent pall of conflict and peril. “Definitely a mix of both,” Alzindani, now 42, says. “Especially as a child.” In the 1980s his village existed at the literal center of a civil war, with opposing factions entrenched on either side of the region where his family lived. Their situation was often in flux, a constant state of turmoil. The rhythms of everyday life, frequently beset by violence or the threat of violence. Alzindani was mostly raised by his mother and grandmother. Well before he was born, his father had begun spending long stretches in the United States, working 12-hour days as a grape picker near San Francisco. He would occasionally return to Yemen for a short stay before departing again for the vineyards. “I didn’t really know my dad,” Alzindani says of those early childhood years. “You’d see him for a couple of months, and then he might be gone for a couple of years.” While his father worked in fields thousands of miles away, Alzindani would sprint home from school, duck into his family’s home long enough to drop his books and grab a snack, and then hurry out to play soccer with friends until darkness fell. Running, back then, for the sheer joy of it. “You did that regardless of the environment around you,” he says. “War or not, you went out there and you were still a kid, playing.” The soccer pitches were rutted and temporary, a series of fields the children appropriated from local farmers. “You played until the owners showed up and kicked you out,” Alzindani laughs, “and then you went on to the next one.” When all of the fields were claimed for crops, soccer was demoted to the village streets, the alleyways, the hardscrabble spaces between houses. It was a gritty, borderless game, but it was always there. “You woke up, and you went to school,” Alzindani says, “but you were always thinking, ‘How quickly can I get home to play soccer?’” Always there, but rarely carefree. Looming over their childhood games was the constant specter of soldiers from either faction descending on the village for provisions. The possibility of gunfire. Sudden artillery shelling. The need, even as children, to have their heads on a swivel. Alzindani recalls times he had to dive for cover to avoid crossfire. How he shielded his head with his hands. Scrambled behind walls. He remembers a day when he and his friends were playing in one of the farmers’ fields and a house next to the field was shelled, sending rocks exploding into the air. “I remember that vividly,” he says. He recalls the sudden, abrupt explosion. Suck of air. Rain of debris and rocks. The dissonance between laughter and sudden terror. The games and the war. The early skill he honed, even then, of holding the tension of opposites.

Coach PJ Mahar found Abdul under the tree at Balboa Park. Then in his 11th year as Fordson’s head coach, Mahar could tell immediately that something was wrong. He’d had other talented runners — thoroughbreds, he called them, including Steve Schell, who’d qualified alongside Alzindani for the previous year’s Foot Locker championship, in 1994 — but Abdul? Abdul was more like a Ferrari. A rare talent, big engine, exceptional turnover. But so finely calibrated that the smallest thing might throw him off. Body awareness, Mahar called it, and most of the time it was a positive thing. Abdul knew his body: knew when to rest, when to push. When it was hurt. Mahar knew about the abdominal pain, of course, but thought it was more likely a torn muscle or tendon along his ribcage, the result of a jarring downhill sprint a few weeks earlier as Abdul pursued a course record on Fordson’s home layout. Either way, stitch or strain, there wasn’t much they could do about it now. For all the miles Abdul had tallied on roads and trails the last few years, he’d logged more in Mahar’s car, traveling with his coach to meets and invitationals. The two had a close bond, forged by hours of highway banter. The runner: eminently likeable, fiercely competitive, committed to all the details necessary to improve. And the coach: big-hearted, a man of few words who knew how to prepare his athletes to be at their best when it mattered most. After all that mileage, Abdul trusted Mahar implicitly. When he explained his pain to the coach, Mahar listened thoughtfully, then tried to settle his senior star. Help him drill back into their plan, draw confidence from everything they’d learned about Foot Locker the previous December. By the time Abdul set off toward the starting line, he felt ready to go. Knowing there was little more he could do, Mahar hustled off to a series of observation points he’d mapped out in advance. First: 200 meters from the start, where Abdul passed in a blur, composed and settled. Then over to an area near a pool and tennis courts, just past the half-mile mark, where Mahar’s wife had written encouraging messages in sidewalk chalk. First, a note from Schell, Abdul’s former teammate: ABDUL, GOOD LUCK And further along, a phrase that was among the first things the Mahar’s infant son had learned to say: ABDUL, ABDUL, YAY-YAY-YAY! When Abdul passed those notes, he was following the plan to perfection. If the chalked words registered, he didn’t show it. He was tucked into the lead pack, hanging off the hot early pace that Karie was setting up front. Also nestled into that group was fellow Michigander Joe Leo, a senior from nearby Detroit Catholic Central who had trained with Abdul in the run-up to the Foot Locker final. Clearly, the shared training between rivals was paying off. Once the field crested the course’s one major hill for the first time — Mahar was at the top, preaching patience — and angled back through the middle of the park, Abdul could feel a growing restlessness in the pack. Karie wasn’t coming back. Did the chase pack have the will to run him down? By the mile-and-a-half mark, the indecisiveness was growing. Abdul knew it was time to make the hard decision. His breathing felt good, no pain in his side. Go now, or let the race slip? Maybe console himself with a top-10 finish? He hesitated a moment more inside the tension of that pack. Weighing the difference between a win and a loss. The difference between good and easy. What it might require of him, to close that gap.

Near the end of seventh grade, Alzindani’s junior high track coach took him aside. “Look at me, Abdul,” he said. Alzindani was still shy then, still lacking confidence around adults. He’d only been in the United States a short time. He barely spoke the language, struggled to read it. But this man had been kind to him, had noticed the aspiring soccer player running effortlessly in gym class and encouraged him to join the track team. He had coached Alzindani to a city title in the 2-mile. The seventh-grader respected the coach, listened when he spoke. “Look at me, Abdul.” Alzindani looked. The coach closed his eyes, held them shut briefly, no more than a moment, and then fluttered his lids open again. Still holding Alzindani’s gaze. “That’s how much you missed the city record by.” Having the time demonstrated was helpful — little more than a blink— but Alzindani already knew the numbers: Four laps. One-point-five seconds. Math was the same across cultures. It was the spoken and written language he found most challenging when he arrived. “I spoke zero English,” he says. His father brought him from Yemen to the U.S. in 1990, when Abdul was 11 years old. Abdul’s mother and the rest of the family remained behind. By then, Alzindani’s father had saved enough money to move to New York City, joining several others in purchasing a combination deli-grocery store. He promptly enrolled his son in a neighborhood school in Brooklyn, where Abdul was miserable. The school was chaotic and disorganized. Alzindani was the target of frequent taunting and bullying, his days filled with a hovering danger that was quite different, but no less awful to an 11-year old, than the violence he’d just left behind. After two dismal months, his father suggested that Abdul move to Dearborn to live with friends from a neighboring village back in Yemen. “He trusted,” Alzindani says, “that they would do the right thing.” It was an astonishingly difficult period: brought to the U.S. by himself to live with a father he didn’t know well; leaving behind his mother, his closest connection in the world; and then being taken 600 miles away to live with a family he’d never met. That family, Alzindani says, “basically raised me like one of their kids.” His father remained on the East Coast to run the business. From middle school onward, the academic year was spent in Dearborn while summers were spent with his father in New York City. Even after his mother and siblings were able to move to the U.S. in 1993, joining his father in New York, Alzindani continued to attend school in Michigan. “I was a really quiet kid,” he says. “I would speak very little in class, until seventh grade in track. And then, you’re winning everything, so you’re almost forced to talk. People are asking you questions. And you’re so excited about winning, it didn’t matter if your English was broken up or not, you just spoke.” Running also became a kind of language. A vocabulary of mutual effort he could share with teammates, even when his English failed him. The sport, giving him a voice in this unexpected place. He also found the Dearborn schools quite different than the one in Brooklyn. “From day one,” Alzindani says, “when I moved to Dearborn I had so many great people that helped me. One individual after another that did one simple thing that allowed me to get to the next thing. And then to the next.” On his first day at the new school, his teacher sat him next to another student who spoke Arabic. The student translated lessons, whispered gentle corrections, nudged Alzindani to keep trying. “I remember him so clearly, encouraging me throughout the semester.” In another class, English as a Second Language, the teacher provided rewards for winning different challenges. Alzindani won a Monopoly game that meant so much to him, he kept the board game well into adulthood. Another teacher noticed his hard work and invited Alzindani to her house to go swimming with her children. “One individual after another,” he reiterates, punctuating each word. The boy in the desk next to him. The teachers. The family that welcomed him into their home. The junior high track coach, blinking his eyes to show a shy boy the opportunity he might seize, if only he could narrow the gap.

Abdul set off after Karie, narrowing the gap. With each stride, he reeled the lanky junior back to him. Near the two-mile point, right before the course looped back past the swimming pool, Abdul tucked into Karie’s wake. 9:43 for two miles. He felt so good then, he was tempted to burst past, increase his turnover, flit across the sidewalk chalk messages — ABDUL, ABDUL…YAY-YAY-YAY! — and make a long, driving push for home. But he remembered Coach Mahar’s admonition: You’re not racing for time, you’re racing for the win. Don’t go crazy. It became his mantra as he and Karie wove toward the second hilly ascent. Don’t go crazy. Run within yourself. There was another mental trigger he’d burrowed into his brain, drifting off to sleep all those nights in his Dearborn bedroom. A reminder related to his strengths as a runner. At his height, downhills were not Abdul’s forte. He figured he might gap Karie on the uphill with his more compact stride, but feared the taller Somali might blow past on the precipitous descent along Upas Street. Wait for the hill, Abdul told himself. Wait for the hill. Clear the hill, and if Karie is still there, make it a final half-mile battle. He latched onto Karie’s shoulder, running stride for stride up the final climb. Neither runner yielded an inch. At the top, right in Abdul’s line of sight when he needed him most, was Mahar. Hollering one more insistent reminder: Follow the plan.

The plan, back in 1994 when Mahar initially devised it with Fordson’s two Foot Locker qualifiers — senior Steve Schell and junior Abdul Alzindani — had been deceptively simple: Have patience. Stay with the pack and let the pack pull you. Wait to make a move until you reach the bottom of the hill the second time, until you’re on the flat angling back toward the homestretch. “Don’t go any earlier than that.” That 1994 race had been the coach’s first trip to the Foot Locker final — his first time in the state of California — and he and his runners could hardly believe they’d managed to qualify two from the same school in the same year. “It was special,” Mahar says. “I knew it then, and I look at it now and —” He chuckles in disbelief. “Yeah, it was something.” Schell and Alzindani had traded wins all season, close teammates intent on beating each other once the gun sounded. “When you watched us at races,” Alzindani recalls, “you would think these guys hate each other. We just went at it. But as soon as the race was done we were best friends. People were always amazed how competitive we were, yet we were so tight.” Training as a tandem through the fall, they knew they were in shape as the Midwest Regional approached, but struggled to imagine how they might squeeze two Fordson harriers into the top eight advancing to San Diego. “We didn’t know if we could make it,” Alzindani says, “but we knew we were competitive.” In the Kenosha race they ran together, hung with the lead pack, kept tabs on each other as the field thinned, and crossed one second apart: Alzindani fifth in 15:20, Schell a stride behind in sixth at 15:21. They were elated afterwards. “You couldn’t wait until you got home,” Alzindani says, “and you couldn’t wait until you woke up the next day and went to school, and you couldn’t wait to call your friends, and…” He trails off, his 42-year-old voice still holding the echo of an ecstatic 16-year old. “When you make it to Foot Locker,” he says, “the confidence you gain from it is just incredible.” Once they got to California, Mahar’s job was to gently temper that confidence. He gathered his guys together the morning of the race and shared his observations from surveying the course. Where to hold back, when to go full throttle. How to be patient. When the gun went off, Mahar says, “Steve followed the plan perfectly, and Abdul…” He pauses a moment, searching for a diplomatic way to summarize Alzindani’s race. “Abdul got a little antsy.” The junior led through the first mile in 4:42, as if he might run away from the field. “I felt so confident off the gun,” Alzindani says. By the 2-mile mark he’d been swallowed by a pack that included eventual winner Matt Downin and runner-up John Mortimer. “It was lack of experience,” he admits. “I allowed the moment to take over.” Alzindani eventually crossed in 22nd place, devastated that his lack of discipline had caused him to fade through the field in the final mile. “He learned a valuable lesson,” Mahar says, “the hard way.” Through his disappointment, Alzindani tried to be enthusiastic for Schell’s accomplishment — eighth place, All-American, barely edging a precocious sophomore from Virginia, Karie — but his own mid-race implosion continued to haunt him. It took most of the tools in Mahar’s coaching toolbox to raise Abdul’s spirits. “Eventually,” Alzindani recalls, “he just said to me, ‘Look, you get another chance next year.’” The words stayed with Alzindani long after he boarded the bus back to the hotel. “That statement was basically in my head for the next 365 days,” he says. “I went to bed thinking about Foot Locker, I raced it every single night, and I couldn’t wait to come back. I wanted to redeem myself.” In case the words weren’t enough, Mahar had one more motivational trick up his sleeve. At the awards banquet, while his two runners socialized in the Hotel del Coronado ballroom, Mahar passed by the table holding the championship trophies and snapped a few photos. Months later, when the 1995 cross country season began, the coach had something for his returning senior. “I gave Abdul one of the photos,” Mahar recalls, “and said, ‘Okay, here’s what we’re working for.’”

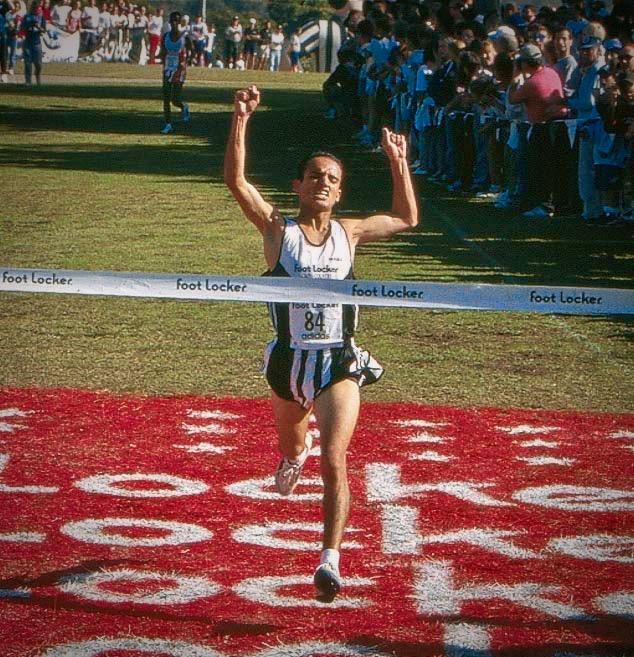

This was it — everything they’d had been working for. Karie was now in Abdul’s wake. Five, maybe 10 meters back as they crossed the flat at the top of the hill. Both were well-clear of the field; it would be a two-man race to the finish. Maybe, Abdul thought, now was the time to go. Maybe Karie could be dropped here. But then he remembered the plan, the bitter outcome when he’d abandoned that plan a year earlier. Even though he felt full of run, ready to surge before the sharp drop along Upas Street, Abdul let Karie close back on him. Leave it to the last half-mile. But then Karie ripped the downhill, legs wide open and churning, much faster than Abdul had imagined. The advantage swung back to the Virginian. Abdul drilled his eyes into Karie’s singlet as they wound back toward the finish, crossed a road, made the final, gradual climb to a wide, raucous homestretch. With 200 meters to go, Karie wasn’t coming back; he’d carved out a 10-meter lead that was only expanding. Abdul’s mind flashed back to that 1994 Foot Locker race. Not his race — Steve’s. In 1994, Schell and Karie had been side by side on the homestretch, and Schell found the extra gear to outkick a kid who would run a 4:08 mile the following spring. Mahar had assured Abdul: If Steve could outkick Karie from that spot, you can too. Abdul dug, grimaced, pulled one more gear from — where, exactly? From a farmer’s field in Yemen. A chaotic school in Brooklyn. A welcoming classroom in Dearborn. A junior high track coach’s blinking eyes. The disappointment from a year earlier. The sign taped to his bedroom ceiling. The countless nights falling asleep with exactly this moment — this final, desperate surge to the finish — playing on repeat inside his eyelids. Fifty meters to go, and Abdul drew even. Then he blasted past, tunnel vision all the way. Somewhere behind him, a spent Karie crumpled to the turf, and then struggled gamely to his feet, but Abdul didn’t know it then. He soared home in 15:12, remembering little about the final meters except his drive for the tape. Karie still managed second, clocking 15:24 after losing 12 seconds on the ground. Only when Abdul reeled though the finish area after the race did the accomplishment begin to sink in. Foot Locker national champion. Another, deeper acceptance came later, alone in his hotel room after his roommate departed for a Saturday afternoon activity. Abdul sat on the bed, and for the second time that day, broke down in tears. The tears came, this time, not only for his improbable, almost unthinkable journey — a national title five years after arriving in the U.S. — but for all of the people who had supported him along the way. The teachers, the mentors, the coaches, the teammates and the competitors that had pushed a boy from Yemen to a championship in California. Alone in a hotel room, the nicest hotel room he’d ever seen, Abdul sat and wept at the wild, implausible enormity of it all.

On a recent Sunday afternoon, Abdul Alzindani prepared to go for a run. He lives in New Jersey now, works for General Electric in the field of renewable energy, has a vibrant, growing family. “We have a basketball team now,” he says, laughing. Five children, ranging in age from 11 months to 11 years. Four daughters and a son. Like many Americans in the midst of the COVID pandemic, he’s been grappling with the shift to distance learning for the children, working from home in his own job. “It’s been a challenging year, for sure.” But when he retreats to his home office, for another Zoom call or a round of email replies, he finds a familiar message waiting at his desk. A single sentence, no longer taped to a ceiling, but propped now next to a computer: Nothing good is ever easy, and nothing easy is ever good. Everywhere Alzindani has gone, from college at North Carolina State University to a series of offices in the corporate world, he’s made sure to display those words. “And when I get back into a normal office at GE,” Alzindani says, “I’m going to have it there as well.” His area of expertise is operational excellence, helping companies reimagine old ways of doing things, showing them how that might lead to innovative, unexpected breakthroughs. At GE, he’s helping to address what is certainly one of the world’s great challenges: global climate change and the need for novel approaches to energy resources. His current focus? Redesigning the renewable energy supply chain. And the same quote that helped propel him to a Foot Locker title has proven valuable in his work of addressing climate change. “It is not an easy task,” he acknowledges, “and I’ve used the quote multiple times. If we’re going to change, it will be hard. And if it’s not hard, we probably didn’t change.” Two decades later, Alzindani tries to brings the same resilience and tenacity to his current work as he did to his pursuit of a competitive running career that ended far sooner than he would have liked. After that 1995 Foot Locker victory, Alzindani claimed a pair of 2-Mile titles, winning both national high school meets, indoors and out. He’s one of only three prep boys to pull off that distance trifecta in a single year since the National Scholastic Athletics Foundation began hosting an outdoor national meet in 1991. The other two? Dathan Ritzenhein and Edward Cheserek. On the heels of that triumphant senior year, Alzindani matriculated to North Carolina State, where he struggled off-and-on with injuries, but still managed to make the U.S. junior team to the 1997 IAAF World Cross Country Championships. Two years later, he came through with an All-America finish at the 1999 NCAA Cross Country Championships, helping propel the Wolfpack to a third-place finish. In the winter of 2000, with the U.S. Olympic Trials in his sights, Alzindani suffered a hamstring injury during a snowy workout on North Carolina State’s track which proved career-ending. Although losing the chance at a professional running career was devastating, his academic focus off the track laid the groundwork for a smooth transition to the corporate world. “You realize that life is short,” he says, “and running is only one component.” After holding positions with a range of companies in the last 20 years, Alzindani felt drawn to the opportunity at GE last spring, at least in part, for the chance to address a pressing global crisis and make a difference in people’s lives. “When you’re doing it on behalf of something that’s bigger than you,” he says, “it makes it a little easier. And when you think about renewable energy — we need to do that. We can’t continue to rely on fossil fuels and other forms of energy that damage our world.” He relates the work to his own children, the world they might inherit. The difference one person can make. It leaves him circling back to the boy who sat next to him in that Dearborn classroom, translating English so he could begin to make his way in this country. The impact that one person had on him. The ways that, even now, he might pay that kindness forward. When he runs these days, the goal is mostly to enjoy the movement, to get in the miles. He has an impressive streak going, his conscientious running habits still intact. “Today will be day 628 in a row,” he says, “without a day off.” There’s no racing for him at this point, no need to follow a plan. Just a desire to find a starting line each day. “My two younger ones love tagging along,” he says. “After my run, I’ll take them out for another few minutes.” And so, on a November afternoon in New Jersey, 2,800 miles and 25 years from an improbable triumph in San Diego, Abdul Alzindani steps out the door of his house to go for a run. Day 628, if you’re counting. When he curves home, there will be children waiting. Laughing, giggling, aching to run. If only for the sheer joy. One more loop around the block.

### More news

1 comment(s)

|