Folders |

An Oral History: A New Generation of Stars Emerged in Jamaica For World Juniors in 2002Published by

The Week the Stars Were BornAn Oral History of the 2002 World Junior Championships in Kingston, Jamaica

A DyeStat story by Dave Devine Photos by Joy Kamani, John Dye and Kirby Lee ________________ Usain Bolt, after a career brimming with gold medals, world records and iconic images, still considers it his “greatest moment.” The meet where he became, as he says, the Lightning Bolt. It was a competition that launched a generation of global athletics stars. Valerie Adams and Blanka Vlasic. Carolina Kluft, Gebre Gebremariam and Nick Willis. Tirunesh Dibaba and Meseret Defar and, yes, Bolt himself. A global championship that featured a callow, unproven U.S. roster destined to scale the heights of the sport over the next decade and a half became a jumping off point. Names like Jeremy Wariner, Bershawn Jackson, and Chris Lukezic. Allyson Felix, Sanya Richards, Sara (Bei) Hall, Lauryn Williams and Lashinda Demus. Two decades ago, on the track-frenzied island of Jamaica, the 2002 IAAF World Junior (U20) Championships opened in Kingston’s newly refurbished National Stadium. For many of the athletes present, those six days offered the sort of stirring, indelible memories that even future senior competitions — Olympic Games and World Athletics Championships — struggled to match. Six days in Kingston, where a 15-year-old Usain Bolt captured the imagination of a country. Where 16-year-old Allyson Felix launched an astonishing, enduring career that concluded at Oregon22. Where a hurdler from Detroit named Kenneth Ferguson and a leaper from Texas named Andra Manson laid down records in the 400-meter hurdles and high jump, respectively, that endure to this day. Where a team of high schoolers and college students, amassed from around the United States, stepped into a roaring, raucous stadium and had to grow up — fast. Twenty years ago, this summer: Jamaica’s 2002 World Junior Championships. This is the story of that extraordinary meet, told in the words and voices of athletes and fans who witnessed and participated. The Voices Allyson Felix – The most decorated track and field athlete in World Athletics Championship history, Felix was a precocious 16-year-old at the 2002 World Junior Championships. Having just completed her junior year at L.A. Baptist High School (Calif.), she competed in the 200-meter dash (5th) and the heats of the 4x100. *Felix’s comments were captured at a press conference before the 2022 USATF Outdoor Championships. Wes Felix – Winner of the 200-meter dash at the 2002 USATF Junior Nationals, Felix was a double medalist in Jamaica, claiming bronze in the 200 and gold in the 4x100. Allyson’s older brother, Wes went on to a decorated career at the University of Southern California before founding Evolve Management Agency, where he serves as an agent for some of the brightest stars of track and field, including Allyson. Bershawn Jackson – Fresh out of Miami Central High (Fla.) in 2002, Jackson won the U.S. junior title in the 400-meter hurdles, then took bronze in that event at World Juniors. He also ran a first-round leg for the gold medal-winning 4x400. An eventual world champion and Olympic bronze medalist in the 400m hurdles, Jackson spent more than a decade as one of the top long-hurdlers and relay specialists in the world. Joy Kamani – Currently the Chief Operations Officer and in-house counsel for the National Scholastic Athletics Foundation (NSAF), Kamani has traveled to numerous international meets, serving a variety of roles for NSAF and USATF. At the 2002 World Junior Championships she was part of the NSAF travel party, submitting daily photos to John Dye for DyeStat.com. Andra Manson – A recent graduate of Brenham High (Texas) in the summer of 2002, Manson won the USATF Junior high jump before soaring to gold in Kingston, where he set a still-standing U.S. Junior and high school record. He matriculated to the University of Texas, winning the 2004 NCAA title and eventually competing in the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, China. Robyn Stevens – Stevens had just completed her first year at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside when she contested the 10-kilometer race walk in Kingston, finishing 18th. After struggling with disordered eating and a series of injuries, she left the sport in 2004 for more than a decade, returning in 2014 to again become one of the top race walkers in the U.S. She won the 20-kilometer race walk at the COVID-delayed 2020 Olympic Trials, and then took 33rd in the Tokyo Games. Lauryn Williams – After winning the 2002 USATF Junior title, Williams went on to claim 100-meter gold and 4x100 silver in Kingston. She had just completed her first year at the University of Miami, where she won the NCAA 100 title in 2004. A decorated sprinter with World and Olympic gold medals, she also claimed Olympic silver in the bobsled at the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics, becoming the first American woman to medal in both the Summer and Winter Olympic Games. Darold Williamson – A soon-to-be sophomore at Baylor University, Williamson won the 2002 USATF Junior 400-meter title and then claimed gold at the World Juniors in the 400 and the 4x400 relay. He went on to win individual and relay NCAA titles for Baylor before claiming Olympic gold and two world titles as a member of U.S. 4x400 relay teams. Mike Byrnes and Jim Spier co-founded the National Scholastic Athletics Foundation (formerly the National Scholastic Sports Foundation) in 1990. Frequent contributors to DyeStat, they often submitted stories from international events like World Junior and Youth championship meets. Their words in this piece are pulled from daily reports filed from Kingston in 2002. Mike Byrnes passed away in 2015 at the age of 83. Jim Spier retired this summer after 30 years as Executive Director of NSAF. He continues to provide recaps from championship meets, right through the recently concluded World U20 Championships in Cali, Colombia.

On Your Marks… Wes Felix: It was such a special meet. Bershawn Jackson: I competed in some Olympic Games, I competed in 7 or 8 World Championships, but the atmosphere in Jamaica 2002, it hits different from any meet I ever experienced as a pro athlete. Allyson Felix: It was the best. The talent of the athletes that competed there…it’s one that I’ll never, ever forget. Mike Byrnes: This meet was the launching pad for most of our sport’s greats. For many Olympic and world champions, as well as world record holders, the World Juniors was their first major competition. Lauryn Williams: Everybody was there with the mindset that we were all going to win and do well. Like, we were going to have a hundred gold medals, because that was just the way we operated. Bershawn Jackson: There wasn’t no egos, there wasn’t no personalities. We were just a whole bunch of kids that felt like we were good and ready to take on anybody. Darold Williamson: Our World Junior team — we talk about it all the time — was one of the best. It was loaded. Robyn Stevens: It was a stacked team. Bershawn Jackson: That team ran deep.

A Bahamian Warm-Up The week before World Juniors began in Kingston, most of the members of the U.S. Junior team spent several days in Nassau, Bahamas — training, meeting teammates, acclimating to the heat, and competing in a two-day competition against fellow juniors from Australia, Cuba and the Bahamas. Lauryn Williams: We went to the Bahamas before we went to Jamaica for like, a training camp. It was my first international trip for a competition. I’d been to Jamaica once before for vacation, but I needed a new passport for this one. Andra Manson: Nothing but good memories…my first international meet. Bershawn Jackson: That was my first international trip, too. In fact, that was the first meet I ever even tried to qualify for — I never went to major meets. We ran summer track, and that was it. Local things. We weren’t knowledgeable about qualifying for global meets. Wes Felix: We got to World Juniors, and it was the best of the best. But getting to know everyone, it was like, “Oh, they’re just like me.” Bershawn Jackson: It wasn’t Allyson, the most decorated athlete of all time; it was Allyson, the kid out of L.A. And Sanya Richards out of Fort Lauderdale. And Bershawn Jackson out of Miami. It was just us as kids…enjoying each other. And not caring about what was going to happen the next week, because we were going to handle our business. That’s the part I enjoyed the most. Wes Felix: When we were in the Bahamas, we could do different outings. Our parents were always big on, “Look after Allyson,” or “Look after each other,” so there was definitely some of that brother-sister dynamic. We went snorkeling; you had all these different stops, and on the last stop, you could jump in with sharks. Darold Williamson: They had sharks in the water, and they lowered this chum bucket. Wes Felix: The bucket of chum is down in the water, and then you have to jump in and hold onto the rope. Darold Williamson: We were all out on this line, watching the sharks feed below us. Wes Felix: I jump in, and Allyson is standing on the edge, all worried. Instead of me protecting her, it’s her protecting me. She was like, “What are you doing? You can’t swim with sharks — you can barely swim!” Lauryn Williams: I don’t actually remember snorkeling — at all. I remember meeting the guys from Australia, and them being super fun…that would be the one thing that stands out about the Bahamas. Bershawn Jackson: We also did this banana boat, I remember that. And the boat flipped over. There was about 10 of us on it. Lauryn Williams: I was, uh…present for that. There was someone who couldn’t swim — that’s how I remember it. Bershawn Jackson: When the banana boat flipped over a girl named Ashlee (Williams) — she was a 100 hurdler — but Ashlee couldn’t swim. She had a life vest on, but she was like, “I’m drowning!” We were all able to laugh because she was fine, but it was just a moment we didn’t care about racing, we were just having fun. Darold Williamson: It was just a fun group of people to be around. Allyson Felix: Such good memories. I met my husband there… Bershawn Jackson: This is a true story, now: I’m the one who set up Allyson and Kenny Ferguson. Kenny was my roommate, and Allyson was next door. So, I’m the one who played matchmaker. Wes Felix: It’s true, they met at that meet. I didn’t know Kenny at all, but she started hanging out with him while we were there, and now…here we are. They’re married and have a daughter.

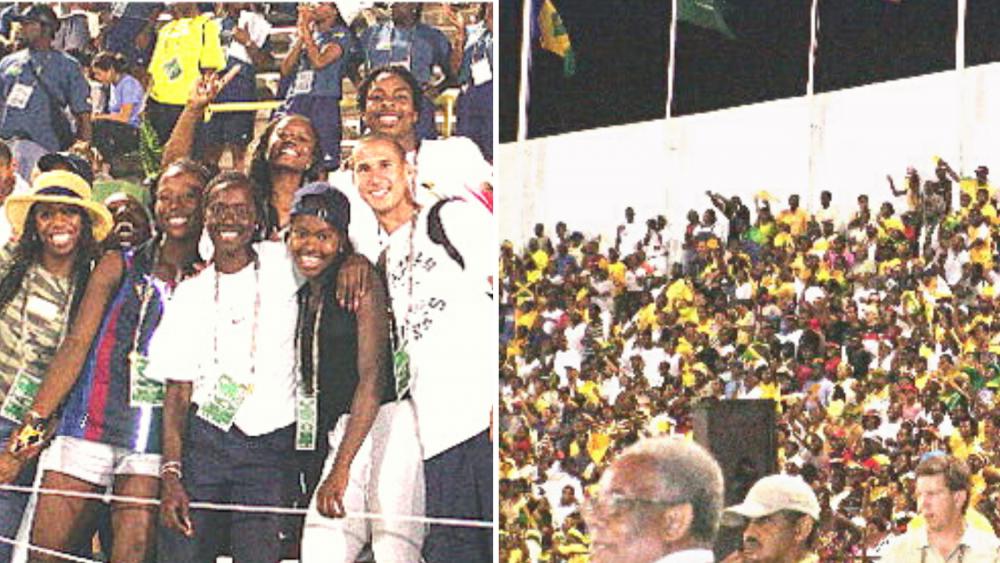

The Electric Atmosphere Arriving to the athlete village in Kingston, the U.S. team discovered austere dormitory rooms lacking air conditioning and window screens, but they also encountered passionate, welcoming fans and a stadium unlike anything they’d seen in the States. Bershawn Jackson: The dormitories didn’t have no AC, so it was very hot. Lauryn Williams: Me and Marshevet Hooker were roommates, and the shower was like…in the bedroom. Robyn Stevens: I remember the dorms had no windows, or window screens, and the beds were super hard. And it was really humid. Darold Williamson: That was the first time I really hung out with Jeremy (Wariner). We were roommates there, and I got to know J — that was the beginning of our friendship. Lauryn Williams: I remember staying up late and talking after the races were over, and the chaperones yelling at us to go to bed. Robyn Stevens: My dad got to know a taxi driver there, and the taxi driver gave him one of those burner phones that he would use to get me out of the athlete village, because we weren’t supposed to leave. The taxi driver took us all over the island, just to show us around. Mike Byrne: When the Championships were awarded to Jamaica, a call went out for volunteers. Three thousand were needed; over five thousand responded. Bershawn Jackson: The energy in the stadium was unmatched. Even to this day, I haven’t ran in a meet where the energy in the stands was — look, you could feel the crowd. You could feel the loud, the horns blowing… Andra Manson: Those horns, man, that’s one of the things I remember to this day. Wes Felix: I’ve still never experienced an environment or an energy like that. Joy Kamani: I only had my little camera. I wasn’t really there to take photos, I was only there to enjoy the meet. But you couldn’t move around, because not only was every seat full, but people were sitting along the stairs, between rows…there wasn’t a spot that you could move into. You were locked in, there were so many people in that stadium. Robyn Stevens: A lot of times I’d hang out with distance runners from other countries. My dream was actually to go to the Olympics in the marathon, so I’d sit in the stands with the runners from Ethiopia and Kenya. Wes Felix: If you didn’t race for four hours, you sat up in the stands and you cheered for your team. Lauryn Williams: It made you feel really cool, like a professional athlete. Because in general, back in the States, you were running around in an empty stadium. Joy Kamani: Not only was the stadium packed, outside of the stadium was packed. There were people I saw climbing the walls of that stadium, to look over and see the meet inside. Andra Manson: The atmosphere was electric. Lauryn Williams: Definitely, the US-Jamaica rivalry was alive and well at that time. And that was one of the things that kind of drove us — We’ve got to be able to perform here, because this is their home turf. Mike Byrnes: When a Jamaican won a heat — wow! The place went crazy. And when they won a medal, forget it. For several seconds, you couldn’t hear yourself talk. Darold Williamson: They were at home, and obviously they were a talented group of athletes in their own right. So, to be there in Kingston, it definitely felt like they had the home court advantage. Wes Felix: All of us, we’re just kids. We’d never been in an environment like that. Bershawn Jackson: For a kid coming from Miami, Florida…I just knew I had a passion for the sport and I was going to Jamaica to run a track meet. But I didn’t know I was going to this type of track meet.

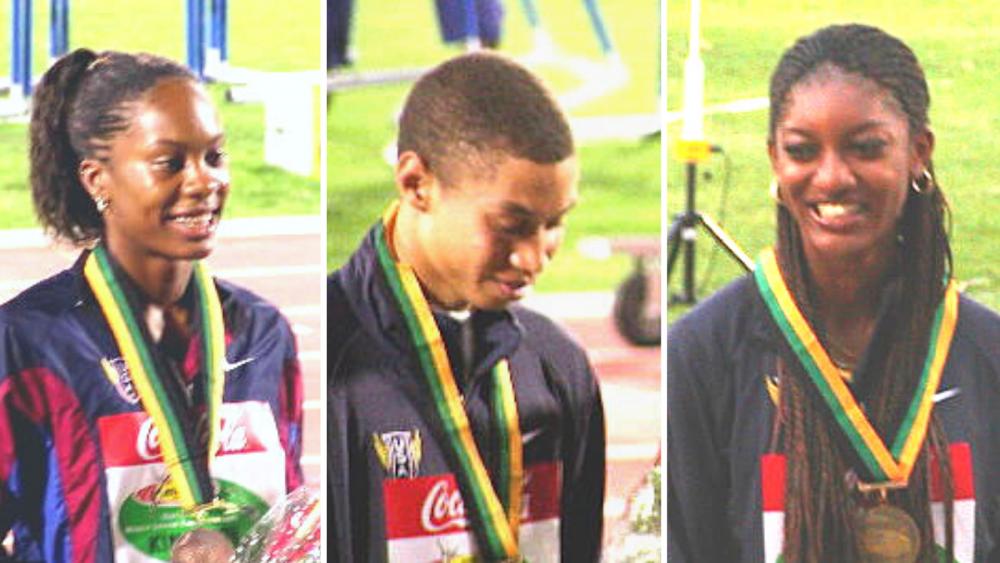

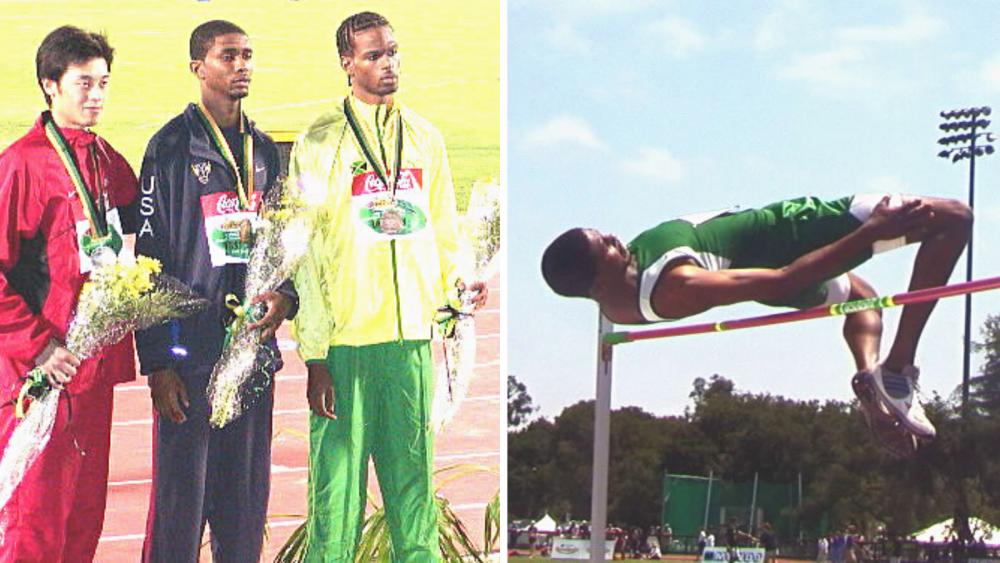

A Pair of Enduring Marks The six-day championship in Kingston provided a host of all-time marks, several national records, and numerous thrilling battles. World Junior records were established by Carolina Kluft (Sweden) in the heptathlon, Lashinda Demus (USA) in the 400-meter hurdles, and the U.S. Men in the 4x100 relay. Each of those marks has since been surpassed, but for U.S. fans, two records have remained untouched for the last 20 years. Andra Manson, out of Brenham High in Texas, soared to a U.S. Junior and national high school record of 7-feet, 7-inches (2.31 meters) in the high jump, clearing 10 straight bars in the final. And Kenneth Ferguson, recently graduated from Munson High in Detroit, Mich., set a still-standing high school record of 49.38 with his silver medal run in the 400m hurdles. (Ferguson declined comment for this article.) Joy Kamani: The high jump competition? I watched that in awe. Jim Spier: The two Americans, Andra Manson and Jesse Williams, looked great. Manson was flawless through 7-3.75. Jesse Williams cleared 7-3, a personal best, but failed on his third attempt at 7-3.75, clipping the bar with his heels on the way down. Andra Manson: In high school at that time, I felt like I was a 7-1 or a 7-2 jumper, you know, with a personal best of 7-4. But mostly in the area of 7-1 or 7-2. Jim Spier: It came down to Manson and the Chinese athlete, Wannan Zhu, in the battle for the gold. Andra Manson: I had a job that summer, gluing mattresses in a factory. You’d glue one side, flip it, glue the other side, and then you’d carry it to another spot in the factory and they’d sew the mattresses together. I’d work the graveyard shift, sleep, and get up to go train for a few hours. Jim Spier: Jamaica’s Jermaine Mason took the bronze on fewer misses at 7-3. Andra Manson: With Jermaine Mason being there, and where the high jump was located, it was loud. He was their hometown athlete, so every time he cleared a bar it was crazy. Of course, they had the horns and everything. Jim Spier: Manson cleared 7-4.5 on his first attempt, with Zhu missing his first. Joy Kamani: Andra would sit down on the bench after each jump and put a towel over head, and he would not move until it was time for him to jump again. Andra Manson: Even just my regular high school meets, I’d clear a bar and then go sit back down. Relax until it was my time to jump. Jim Spier: Zhu missed twice again to give the gold to Manson. Manson then moved the bar to 7-5.25, and... made it on his first attempt! Joy Kamani: He’d just get up, walk slowly over to his mark, and jump. And then sit down. He never once got up and did any kind of routine — nothing. Jim Spier: Over again on his first attempt at 7-6, equaling Dothel Edwards’ high school record. Then, on to 7-7: over on his first attempt for a new high school record and a US Junior record! Andra Manson: I think it was 14 straight heights, from the prelims to the finals. Jim Spier: Where now? On to 7-7.75. He was under the bar on his first attempt; a poor miss on his second. He packed it in then, calling it a night. Andra Manson: There were guys, over the years, that I figured would get it. I mean, records are made to be broken, so I’m sure someone is going to get it at some point. I’m kind of surprised it’s lasted this long. The men’s 400-meter hurdle final took place near the end of Day 4, shortly after Usain Bolt had dazzled the home crowd with a victory in the 200-meter dash. Ferguson, the more experienced 400-hurdler among the U.S. pair, looked headed for victory until the South African, Louis Jacobus “LJ” van Zyl, drew even on the 10th hurdle. Bershawn Jackson: I remember this race like it was yesterday. Jim Spier: Both Americans, Bershawn Jackson and Kenneth Ferguson, were out fast, one-two at the top of the back stretch. Bershawn Jackson: I was already “Batman” by then. I got the nickname when I was 10 years old. They said I had big ears and they fly when I run, and it kind of stuck with me. It’s one of those things where I was quiet, and I was fearless, and I had a huge heart — the Dark Knight, right? Jim Spier: Jackson took the lead at the top of the turn with Louis van Zyl of South Africa between the two Americans. Ferguson began his charge over hurdle seven to take the lead. Bershawn Jackson: Kenny was an exceptional athlete. He was a big dude, and he was fast. Jim Spier: Van Zyl, now in second with Jackson fading, began his charge, and caught Ferguson at the 10th and final hurdle. Bershawn Jackson: LJ van Zyl? We had no idea this kid was about to run 48 seconds. Jim Spier: Van Zyl then lengthened his lead to win going away in a spectacular 48.89, a PB by almost 1.5 seconds. Kenneth Ferguson and Bershawn Jackson were both under the old high school record. For Ferguson, 49.38, destroying the 18-year-old record held by Patrick Mann (Gar-Field, Woodbridge, Va.) of 50.02 (and the hand-time by Bob Bornkessel of Shawnee Mission North, Overland Park, Kan., in 1968 of 49.8). Bershawn Jackson: What me and Kenny brought to the table was a little different than kids do now. We wasn’t afraid to go out and compete — we didn’t care about lining up. So, why haven’t kids broken it this far along? It’s puzzling, because I would’ve thought by now the record would’ve been knocked down. But hell — 20 years later, man, Kenny’s record is still here.

The Beginning of Bolt The Jamaican World Juniors gave rise to a pair of sprinting greats who would accumulate global laurels at an astonishing rate over the next two decades. Usain Bolt, just 15 at the time and making his international debut, had the more successful meet in Kingston. Allyson Felix, 16 years old in Kingston and already on her second U.S. team, continued to win global medals right through this summer’s World Athletics Championships in Eugene, Oregon, but battled a nagging injury in Jamaica. She took fifth in the 200 final and bowed out of the 4x100 after the opening round. Within two years, both would be international stars in the sport. In Kingston, Bolt competed in three finals, running second leg on Jamaica’s silver-medal 4x400 relay in addition to the 200 and 4x100, but it was the latter two in which his emerging talents shone the brightest. Allyson’s brother, Wes, had a close-up view of Bolt’s emergence in both events. Wes Felix: Honestly, I had no idea who Bolt was. I had no clue. Jim Spier: I’m not quite sure I’d ever seen anything like this before: a 6-foot, 2-inch, 15-year-old running 20.58 in the first round, jogging the last 20 meters. How can Usain Bolt not be declared the favorite, especially in front of his countrymen? The only reason anyone else was within a half-second of him was because he slowed at the end. Wes Felix: He was just this Jamaican kid that was a big deal to them. We knew he was fast, but there was no real intimidation factor. Bershawn Jackson: For the Jamaicans, Bolt was the man from Day 1 — they loved him. Wes Felix: A thing that I always envied is that he was having fun. Like, he was actually enjoying this. He was 15, and he wasn’t nervous; he didn’t seem to carry the weight of the world on his shoulders. Bershawn Jackson: I remember they sold out of tickets, and you had people jumping over the walls to get in, because it was the 200 finals with Usain Bolt. Someone said the fire marshal threatened to shut the meet down. Jim Spier: This race took place immediately after the women’s 200 meters…the place was rocking. Everyone in the race had run 20.97 or better. Bolt did not get an especially good start. In fact, Bruno Pacheco of Brazil, one lane on Bolt’s inside, appeared to get the best start. Bolt was third coming off the turn, but then he put on a big charge. Joy Kamani: He was just gone. Amazing. Jim Spier: Brendan Christian of Antigua tried to catch him, but Bolt was on his way. Wes Felix: I remember getting into the homestretch and just holding on for dear life, feeling like, “Whoa, I might get a medal.” Jim Spier: Christian managed second in 20.74, and a consistent Wes Felix took third…the noise level during the race was deafening. Wes Felix: That’s when Bolt said, “Hello world, I’m here.” It felt like being a part of history. Bigger than just sport. It felt bigger than winning or losing or setting a record. Joy Kamani: You thought — My God, if he had run through the line, what would he have run? Two nights after the 200 final, on the closing evening of the 2002 World Juniors, Bolt lined up to anchor his Jamaican 4x100 squad against a loaded U.S. team. There were 35,000 fans in the stands. The U.S. line-up was Ashton Collins to Wes Felix to Ivory Williams to Willie Hordge. It was Felix’s 19th birthday. Wes Felix: My clearest memory from Jamaica is standing in the tunnel, going out for the 4x100. At this point, Bolt had already won the 200. We’re there in Kingston, the national stadium was completely full. People were literally climbing over the walls. Mike Byrnes: Once again, the crowd drowned out the announcer’s lane assignments. Wes Felix: You walk out and put your mark down on the track, and the whole stadium is on their feet cheering. Erupting. And then it gets dead silent out of respect for the race… and then the gun goes off. Mike Byrnes: Collins got out about as well as can be expected, but trailing. Wes Felix: I was second leg, so you just hear the energy of the crowd and you’re trying to make sure you can focus on your mark. Mike Byrnes: Felix holds his own, and going into the third leg, Jamaica and the US are even. Wes Felix: You run through, get it off to the next guy, and you’re just excited you didn’t ruin the race. Mike Byrnes: Ivory Williams runs a brilliant leg, and hands off two meters in the clear. It appears the Jamaicans have a tough time on the final pass… Wes Felix: The stick gets to our anchor leg, Willie Hordge, and it’s him going up against Bolt, and everybody is just losing their minds. Mike Byrnes: Hordge is gone. Joy Kamani: I will never forget Usain Bolt trying to run down Willie Hordge, and he could not get it done. Wes Felix: We win and break the record, and the really cool thing is that the fans were so appreciative. They still loved you. There was just this beautiful respect. Mike Byrnes: The U.S. team ran into the history books with a World Junior record of 38.92, a great birthday present for Wes Felix. They put down the home team Jamaica’s 39.15, led by 200-meter gold medalist Usain Bolt, and Trinidad & Tobago’s 39.17, led by 100-meter winner Darrel Brown. The silver and bronze teams both set new national junior records. Wes Felix: That was a moment I don’t think I’ll ever be able to forget.

Legacy & Longevity The impact of the 2002 World Junior Championships radiated for years afterward for U.S. team members. There were numerous records, titles and podium appearances for alums from the squad. Perhaps most impressively, three women from that 2002 U.S. roster were still competing at this summer’s World Athletics Championship in Eugene, Oregon. Twenty years after appearing in Jamaica, Allyson Felix competed on the bronze medal Mixed 4x400 relay and ran a prelim leg for the gold medal-winning 4x400. Sara (Bei) Hall finished fifth as the top American woman in the marathon. And race walker Robyn Stevens, breathing second life into a career that had been shelved for more than a decade, took 24th in the 20-kilometer Race Walk. Andra Manson: It’s longevity, it’s the mentality — staying focused for that long. In track and field there’s always somebody younger and better coming of age, so to maintain that through college, and then another 16-plus years…hats off to all three of those women for still competing, staying focused and keeping that drive. Wes Felix: In a lot of ways, that World Junior meet set the tone for a life that Allyson and I still live today. Traveling overseas and going to meets together — that was the first time we ever did it. Robyn Stevens: I remember Allyson was really young, it was her first team. We knew she was going to be a legend if she stayed in the sport. Darold Williamson: It’s really cool when I see Allyson still competing. I remember she seemed like the young one in the group, and I guess she was. Robyn Stevens: Sara Bei — now Hall — was always a strong runner; she was the runner to beat, even back then. We raced each other in high school. And I think part of her story is that she has yet to make an Olympic team, so she’s like “I am not going to quit until I make an Olympic team.” Bershawn Jackson: It takes a lot of dedication. I raise my hat, because it shows their resilience. Robyn Stevens: My path was different. For me, it was all an accident when I came back. I retired in 2004 because of an eating disorder and an Achilles injury. The college experience was a huge disappointment from an athletic perspective. I stepped away to try to get healthy again…I had no intention to return, although I missed competing for Team USA. And then in 2014, I hit my head on a door and got a concussion…my doctor didn’t want me running, biking, or swimming, but she was like, ‘You used to race walk, right? Maybe try doing that.’ That was how I accidentally returned. Lauryn Williams: It’s impressive, even 10 years later. It’s unlikely 5 years later, so to see 20 years later and this is literally the best of the best…I think some people don’t appreciate it. Darold Williamson: It should be pretty motivating for a lot of young ladies that look up to them. Wes Felix: There were so many people in Jamaica that went on to do so much in the sport, for such a long time. Bershawn Jackson: You’re talking, three years later, our generation took over. Darold Williamson: It was a successful meet, a lot of fun, but more importantly — one of the things I always think about is the people who were there at that World Junior meet. It was the beginning of careers for a lot of people. Andra Manson: We were all around the same age…a lot of those athletes we’d see each other later. It’s where you made those relationships. Allyson Felix: So many of those athletes are close, lifelong friends. Bershawn Jackson: It’s an amazing journey. I was just at the U20 Trials and (my daughter) Shawnti won the (100-meter) trials. And so, I’m like, “My baby is about to go to the U20 Worlds.” It dawned on me that I won U20 Trials 20 years ago — and 20 years later my daughter wins. Allyson Felix: I can’t believe it’s been 20 years…that’s crazy. But such good memories. Bershawn Jackson: Allyson has actually raced my daughter. That’s just one example of how long she’s been around. Lauryn Williams: You talk about full-circle. Twenty years later, and I’m the manager of this year’s World U20 team. Wes Felix: Whenever we see each other, we always bring it back to Jamaica. It was, for almost all of us, our first trip. It was — for sure — our best trip. The one that was the most fun. They became truly lifelong friends. Joy Kamani: When kids go overseas, especially at that young age…it gives them a great appreciation of the world we live in, and an acceptance and understanding of other cultures. We need to do that more. Andra Manson: Being part of that team was very special. Bershawn Jackson: People ask me what’s my greatest experience in track and field, and I’m going to say the World Juniors in Jamaica. Joy Kamani: I’ve been to each World Junior (or U20) meet since then, except during the pandemic, and nothing could touch Jamaica. Nothing. Because the love for the sport is so immense there — it’s untouchable. More news |