Folders |

Backstage With Untold Track and Field History: Bill McClellon And His Rise Toward 7 FeetPublished by

Probing the Artifacts ****** The Unlikely Ascent of the First High School 7-Foot High Jumper By Marc Bloom for DyeStat [Part One of Two] On December 14, 1963, the 9th Bishop Loughlin Games were held at the New York Armory in Washington Heights, with their usual slate of varsity and novice events that took a full day and part of the night to complete. It was the traditional opener to the area’s high school indoor track season and there was much excitement in the region to get back onto the wooden 220-yard oval, host of many of the nation’s best athletes each winter. While the running events always took center stage, this day was different. The varsity high jump would create track and field history. But that was only because it was linked to the novice high jump, which would also create history — a grander history seemingly left untouched for generations like a fossil remaining to be dug up, dusted off and scrutinized. The two high jumps were bonded in memory, a window into formative and daring achievements in an era when sprinters sprayed a sticky substance like hair spray onto their flats for a bit of traction on the slippery Armory surface, laid down packing tape for starting blocks, and waited for the crack of the starter’s pistol while inhaling the pungent aroma of grilling hot dogs at the food concession only a few feet away. There was no precedent for what happened jointly in the two high jumps that day, and there has likely been no repeat of it since. The two jumps, like mirror images, are welded in the pantheon of Armory legend. While the Armory itself has been remade into the modern architectural marvel we know today, these jumps floated in the untapped haze of distant memory, ripe for excavation if only the protagonists could be found almost six decades hence and asked how it was on that day, during those moments, when they were still learning the tools of their trade, that they managed to leap so high. I competed myself at the ’63 Loughlin Games, starting my senior year of track on a second-string mile relay. At the time, I was also several months into the start of my journalism career, sending results and stories to Track & Field News, receiving an official T&FN press I.D. from the managing editor, and following the top athletes like a hawk.

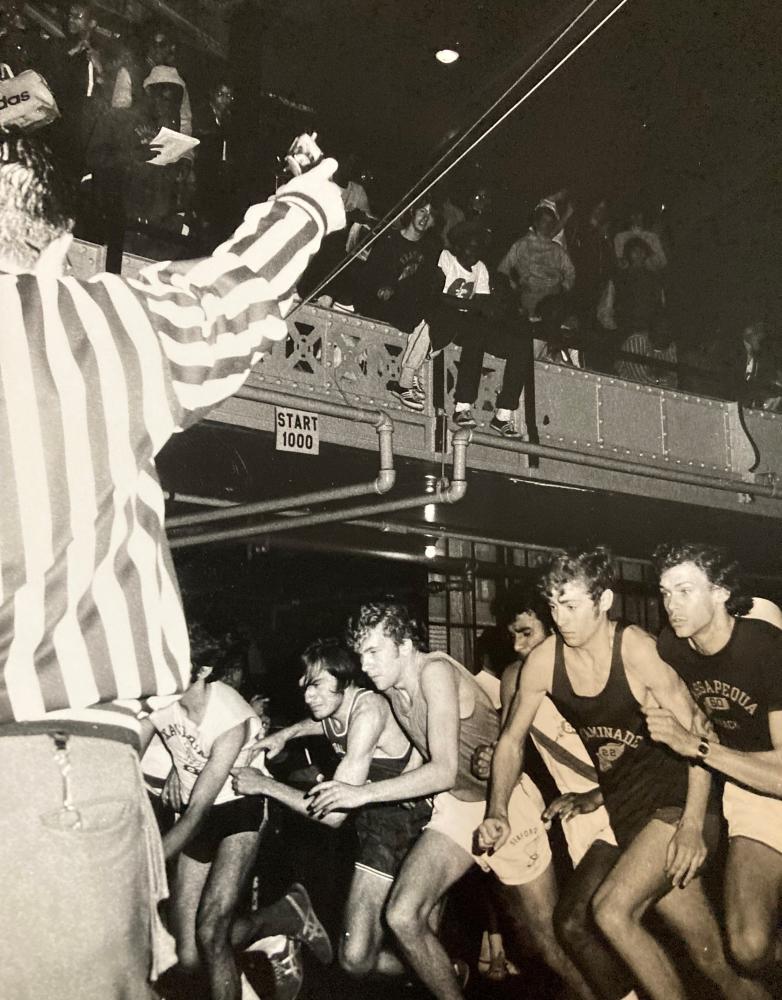

Drills over, a little spit and polish, and you had a track arena: same wooden floor; same hot dogs. We were safe inside the place. Who was going to mess with anyone with a tank at his disposal? I watched the historic twin high jumps but with one eye, retaining little as the two events unfolded that day. Numb with anxiety awaiting my late race — it didn’t go off until that night’s “Fugitive” episode was long over — I could claim only the vaguest recollections: mainly the aftermath when one of the winners was pulled aside by reporters for interviews. My attention was always drawn to the working press. You could say that with divided loyalties that day I covered the high jumps with my heart, and decades later my heart cried out for some closure. Could I find the protagonists, both my peers from an age standpoint, and bring to life not only their fateful encounter that day but the broad arc of their storied careers? Could I satisfy not only journalistic inquiry but a personal longing of more than half a century to understand how these two young men were brought together in an unlikely denouement right under my young journalistic nose: a nose tickled by the lusty hot dogs and sharp mustard while I sat with teammates, holding the baton as designated lead-off man, in long rows of foursomes waiting for the dregs of the mile relays to be summoned, so we could rise and shake out our legs while darkness descended over Broadway. After some help from a college athletic office, I found the varsity jumper in retirement in the Florida Keys, a short drive from Key West, where he lived with his wife. After some help from my younger daughter who is a whiz at social media, I found the novice jumper in western Ohio, also in retirement, where he lives with his wife. Both have children and grandchildren. Both were willing to go into their pasts. The quest of springing off a dead planked surface beyond a height over their heads and into a waiting pit was but one thing the two youngsters had in common that December day. Another was being uprooted as a child. One, African-American, left North Carolina alone at age 5 in a searing departure for a new home in Harlem. The other, blond, of Latvian and German heritage, left post-Nazi Germany, also at 5, with his family to start a new life in America. It was 1952. The world was in transition. Attempts at renewal were everywhere. These two five-year-olds were carried along by family history to unknown territory and, in their different ways, toward a rebirth. Looking back on the 1963 Loughlin meet, I’m a little surprised it was actually held. The JFK assassination was only three weeks earlier and the nation was still in mourning and on edge. The placid ‘50s had given way to a decade of turbulence, racial unrest and the Vietnam War. New suburban living had led to planned communities of middle-class conformity, especially, in the East, Levitt homes known as Levittown, first on Long Island, then in Pennsylvania, outside Philadelphia. On that December morning, Karl Kremser from Woodrow Wilson High School — since re-named Harry S. Truman — in the Philly-area Levittown, piled into a station wagon with teammates for the hour-and-a-half drive to the Armory with their coach Bud Grossman. Kremser was a senior high jumper struggling to clear 6 feet. As a junior, he couldn’t match his older brother or just about anyone else. “I could never break through,” he told me. “I could barely make the opening height.” Grossman had talked up the Armory as the place to be: The kinetic atmosphere, the top-flight competition, the fans in spontaneous revelry, bringing the blues from the streets into the balcony to fashion one big, outlandish roar as the athletes spun magic around that bare bones track. Kremser thought to himself, “Maybe this was it, what I needed; to compete against the best.” Could some Armory dust sprinkle Kremser with enough confidence to give his legs the spring to join the 6-foot circle and pick up a top-three medal? At the time, only a handful of jumpers cleared 6 feet consistently, especially on that floor without the aid of spikes, not permitted and of no use anyway with the resistant gym-like surface. Then, most of the city’s high jump records were held by Del Benjamin of La Salle Academy in lower Manhattan, who set a national freshman outdoor record of 6-3.75 in 1961 and national sophomore outdoor record of 6-7.25 in 1962. Benjamin held the Loughlin meet record of 6-4.50 set as a junior in December, ’62. The national indoor record at the time was 6-7.50 by John Thomas of Rindge Tech in Cambridge, Massachusetts, set in the 1958 AAU National Scholastics at Madison Square Garden, where spikes were permitted. Thomas, a towering 6-foot-5, became one of America’s biggest track-and-field stars at a time when Sports Illustrated showcased key meets on its cover. In 1959, as a Boston University freshman, Thomas became the first man to jump 7 feet indoors. Thomas went on to many storied duels with Valeriy Brumel of the Soviet Union. In a Cold War rivalry, Brumel won 1960 Olympic gold over Thomas, who took the bronze; and the 1964 gold over Thomas, second on misses. Kremser, an all-around athlete who also played midfielder on the school soccer team, was aware of Brumel and his aura. “I remember seeing a picture of him,” said Kremser, who stood 5-11 in high school. Brumel was 6-1. “I had a hard time touching the basketball rim, and he could touch it with his toe.” Today it might be hard to imagine any way of high jumping other than the Flop. But Dick Fosbury’s revolution was still some years away. Kremser, Thomas, Brumel, from high school to college to the Olympics, all jumpers of note did the “straddle,” or some version of it. Indeed, the straddle, with its measured approach, frontal assault, and lift-off some distance from the bar, attempting to harness the center of gravity in midair, was about as opposite from the tight, back-flipping, leg-snapping Flop style as one could get. Coach Grossman worked with Kremser on his technique. He took a seven-step approach, typical of the period, with a run-up of four steps and three more, as he put it, “at the bar.” Kremser leaped off his left foot and led with his right foot over the bar. At the Armory, Kremser and other jumpers took a hint from the sprinters, spraying “stick-em” on their soles for traction. The high jumpers were in good hands. Kremser remembered an “old, white-haired gentleman” who ran the event with precision. I remembered him too, but not by name. He was impresario of the high jump, with a soft touch. The Loughlin Games, even then, featured over 4,000 athletes from 150 schools, and the high jump field was filled to capacity with more than 50 entrants. “With so many competitors,” said Kremser, “you had to learn how to pace yourself. You’d get revved up to jump, then had to calm down and wait.” Jumpers missed, some cleared. More misses, a few clearances. In the fog of time, Kremser, now 76, recalled that he would have started jumping at no higher than 5’ 8”. After a few hours of elimination, Kremser was among the final contestants still standing. And he’d nailed a PR with a jump over 6 feet. One by one, the other jumpers failed. Maybe it was the miracle workings of stick-em, or maybe it was the highly-charged atmosphere — fans leaning over the balcony, banging furiously on the metal overhang, that Kremser said psyched him up — but whatever Armory magic graced him that day, Kremser’s body levitated toward the Heavens, beyond 6 feet, 6-1, 6-2 and 6-3 to conquer the bar at 6-4, high enough to become 1963 Bishop Loughlin Games high jump champion — the varsity high jump champion. One day you’re struggling to clear 6 feet, the next you’ve scaled 6-4. One day you’ve got a pitchfork in your hands at practice to smooth out the sawdust in your high school pit, the next you’re in the high school track-and-field capital of the known universe tumbling into a safe landing amid the boisterous cheers of a hot dog-eating throng. The bar was then raised to 6-5 and eventually re-measured at 6-5.25. Kremser steadied himself. He’d already achieved the impossible. The boy whose father, conscripted by Germany, was injured fighting in the War at the Russian front; whose family would become refugees in the U.S., first settling in New Jersey near a place called Seabrook Farms, which hired his father among other marginal workers, and had provided much of the food for American troops in battle, had acquired a slice of the American Dream. Kremser missed twice at 6-5.25. Or did he? Kremser can’t be sure. Frankly, I have no idea. I may have been waiting my turn at the Armory lavatory then. What we do know is this: On his successful attempt, Kremser took his run-up, propelled himself skyward, using his arms for leverage, curled his right foot up and over the bar, sensed air under his midsection, toppled over with his trailing leg clean and plopped into the rudimentary rubber pit. Clearance! The Kremser family understudy had broken out. Kremser’s 6-5.25 jump shattered Del Benjamin’s meet record and was high on the list of best performances ever recorded indoors in the New York area and beyond. Looking back almost 60 years later, Kremser was still amazed at what he achieved that day, and under those primitive, barn-like conditions. But maybe it was those conditions above all else that made the difference to the impressionable teenager. He paid homage to his coach. “Grossman took us out of our regional area to come to the Armory and test ourselves against the best,” Kremser said. “You had to learn how to compete in that atmosphere.” With a gold medal in hand, a remarkable new PR, revised goals and thoughts of jumping 7 feet one day, Kremser settled in for the rest of the meet with a few of his teammates left to compete. It was his turn to smack the balcony, and take a look and see how the novice high jump would turn out. Before long, the white-haired gentleman with the clipboard rounded up the novice jumpers. Maybe I was back from the bathroom because I have this rusty image: a starting height under 5 feet, awkward kids learning as they went, head-first dives over the bar, some boys in basketball or tennis sneakers, many not knowing the rules, like you got three jumps. The white-haired gentleman had his hands full. And then he arrived, like the phantom he would always seem to be: above the fray, in his own world, long legs with compact trunk, built not like a Brumel or Thomas or anyone, a singular figure, with a glow on him; wherever he stood, the light shown, finding its way through windows from above untouched in a century, all velvet like Sam Cooke, the light, the stage, the spot on the approach that was his, the short, five-step style, the smile — that’s what Kremser remembered, the smile. “He had this big smile on his face,” Kremser said. “He couldn’t stop smiling.” Bill McClellon. The novice. What was William Edward McClellon, a sophomore at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, smiling about? Maybe, for one thing, because he somehow managed to be accepted into Clinton even though he did not live in the Bronx. Clinton was a much sought after school. McClellon’s home in Harlem was an hour away via subway. “I never knew why I went to Clinton,” McClellon, 75, told me, as we spoke for the first time since 1966. “But I always considered it divine intervention.”

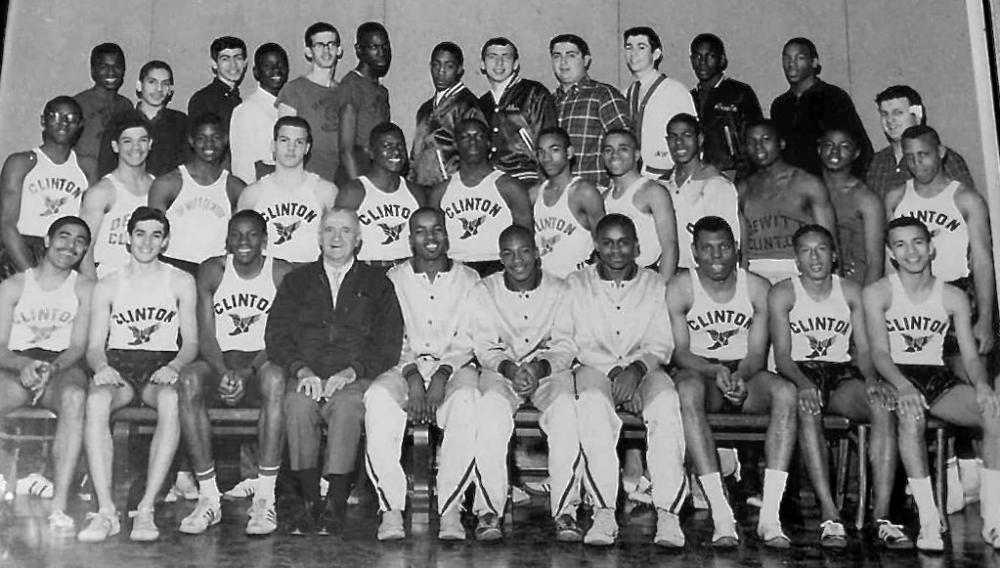

Divine, indeed. Clinton, which celebrated its 125th anniversary this past May, had one of the best track coaches in the city, the veteran Charlie Scher, and was an all-boys academy then considered a jewel in the public school system with a history of over 10,000 students in the 1930s, and scores of celebrated alumni. From the arts, sports, fashion, Hollywood, Broadway: James Baldwin. Richard Avedon. Tiny Archibald. Paddy Chayefsky. Irving Howe. Robert Klein. Burt Lancaster. Ralph Lauren. Garry Marshall. Sugar Ray Robinson. Richard Rodgers. A. M. Rosenthal. Dolph Schayes. Neil Simon. And Gary Gubner, high school indoor record holder in the shot put who became an Olympian in weight lifting. Who didn’t go to Clinton? Maybe McClellon couldn’t stop smiling because at 16 he’d gotten his life together after a rough start, saved it seemed by the high jump, which he’d tried out at a reform school for wayward boys in upstate New York. Bill was born in Chatham County, North Carolina, the geographic center of the state. He never knew his father. He had no siblings. His young mother picked up and moved to New York for a better opportunity, finding work in a Thom McCan shoe store in Harlem. She left Bill with her mother, his grandmother, Esther, whom he adored. Two younger cousins also were cared for by Esther. The three boys played and ran carefree in the racially mixed rural area. Bill walked five miles round-trip to school. He was happy. At 5, his young life was torn apart when his mother, Sadie, sent for him to come join her in Harlem. Bill missed his grandma and the open country life. “Being in New York was culture shock,” McClellon said. “I had issues.” In time, those issues boiled over into rebellion. In fifth and sixth grades, instead of going home after school, McClellon would ride the subways for hours, contemplating his place in a threatening world, trek to Coney Island, hit the rides until closing time, travel the subways some more, and usually be picked up by the police at late hours and brought home. “I became a truant, a runaway,” he said. To try and straighten out, McClellon was sent to the Wiltwyck School for Boys, a home for troubled youth, located in the town of Esopus, about a 90-minute drive north of Manhattan. Typically, the boys came from broken homes and were deemed in need of supervision: corral a minor problem before it gets worse. Heavyweight boxing champion Floyd Patterson was a former resident. Eleanor Roosevelt was a key benefactor. McClellon entered at 10 and stayed for two years. The boys were allowed home on weekends and Bill would take a commuter train back and forth to Harlem. The sprawling campus was more of a camp than a juvenile detention, at least to Bill, who recalled activities like horseback riding. Looking back, McClellon said that while the school lacked something sorely needed — psychological counseling and help with anger and other issues — therapy of a different kind was provided to McClellon via a makeshift high jump set-up. Someone had given Bill a coaching manual by Ken Doherty, the former national decathlon champion, Hall of Fame college coach and meet director of the Penn Relays. After McClellon was drawn to the high jump section, counselors set him up with a standard, crossbar and sand landing pit. Bill studied Doherty’s advice. “It was lights out at 9,” said Bill. “I would get out of bed when everyone was asleep and do exercises like squats that the book said were good for the high jump.” All Bill had was tennis shoes but he made the best of it. With the risks of crashing into the sand pit, McClellon’s initial style was something out of the old scissors technique, to protect his landing. In two years, McClellon left Wiltwyck for junior high in Harlem. He had no grandiose goals, no real sense that the high jump was his baby. But he felt more secure: no more truancy, late nights, or subway trips to Coney Island. His school had field days with a high jump. Bill tried it. Maybe he did 6 feet, or 6-2 as one newspaper report claimed, maybe not. He could not recall. Entering Clinton in 10th grade, his friends went out for football. At 155 pounds, McClellon demurred, choosing track. In tryouts, he met coach Scher, who took one look at the young man with racehorse legs and told him, “You’re a high jumper.” Bill was so high-waisted his teammates called him, “Turkey.” It was said with affection. One would think that with all the wealthy alumni, Clinton sports would lack for nothing. But the track team had no high jump apparatus and, for a track, only a tight oval in the balcony above the gym, common in the city at the time. For practice, year-around, most of the team walked 45 minutes to the Van Cortlandt Park outdoor track, then cinders, a short jog from its cross-country trails. McClellon would run those trails, hills included, indeed the entire 2.5-mile high school course, partnering with the team’s distance runners. “For the endurance,” he said. Later in college, McClellon even ran a couple of cross country meets. That was McClellon: no drama, task-oriented, cover all bases, work with what you had. He did the requisite conditioning, strength work and plyometrics, improving his musculature. A field event specialist at nearby Manhattan College, Irv Kintsch, helped McClellon refine his jumping technique and took him up to the Riverdale campus to work with a real pit. “I had good technique,” McClellon said. “I just had to trust my physicality.” By the time of the Loughlin Games, his first high school meet, McClellon, in practice, had finessed a shorter-than-usual, five-step straddle style. He would jump from the right side, off his right foot, positioned about an arm’s length from the standard, and in his upward spring try to get his center of gravity even with the bar as he executed his clearance, lead leg then trail leg, before rolling into pit. At the moment of clearance, his sweet spot, McClellon’s head faced down above the crossbar, his left arm extended outward for balance as his trailing knee swung over, leaving the bar intact. With the Van Cortlandt practice pit consisting of the same saw dust and sand as at Wiltwyck, McClellon had to watch his back, literally, and jump below his ability, barely touching 6 feet. At the Armory, when Bill joined the novice contingent, he had no jump on record, no one knew who he was, least of all Kremser, and it’s doubtful his coaches had any realistic idea of his potential. McClellon started his jumps without a blemish at 5-8. The bar went up to 5-10 and then 6-0. McClellon cleared easily. “I was feeling my way through,” he said. The bar was then raised one inch at a time. It took hours for the field to be eliminated. At 6-2 or 6-3, as he recalled, McClellon had won the event, so far with no misses.

Don’t mistake that cool-ness for bravado. The boy who once seemed abandoned had found himself and would not let go. Take me higher: 6-4, 6-5, 6-6. All perfect. With that rare gift of unerring confidence leavened with an ability to focus and tune out the hubbub of Armory commotion, McClellon stepped up to attempt 6-7. He made it on his second try, the beginning of a rock star aura that would envelop him at every meet, everyone waiting for the compelling moment when the high jump— the varsity high jump — would get under way. The white-haired gentleman was in the spotlight too. Every height, every new record, week in and week out, had to be measured to perfection, affirmed for posterity. That December day, McClellon took three tries, all misses, at 6-8. Did he meet Kremser afterwards? McClellon could not recall. Kremser, who’d watched McClellon’s performance in awe, said yes. “We talked. I wanted to congratulate him. Bill had unbelievable spring. I was envious.” Karl Kremser had won the varsity high jump with a meet record and national-level performance, but Bill McClellon, in the novice high jump, had won the day, and begun one of the most heralded careers in high school track and field. McClellon’s mark was a national sophomore indoor record. Novice or not, he had not come out of nowhere. He had it all figured out. For all his power, McClellon fashioned a bewitching presence, all the more captivating when he would take to finding a broom and sweeping the high jump area of dust, a spot of water, an errant spike, cleaning house, as it were. “I didn’t want to slip,” he said. At times, Bill would nap with one eye open while the field took hours to whittle down, rather like the indulgence of gold medalist Mutaz Essa Barshim, caught by an NBC camera in repose, at the recent world meet in Eugene. The rest of McClellon’s sophomore indoor season of 1963-64 went like this: *Jan. 19, Cardinal Hayes Games at the Armory: Jumped 6-7.75 to better John Thomas’ national high school indoor record. He also tied the Armory all-time “open” record set in 1947 (on the weekend of my birth; I missed that one) by collegian Irv “Moon” Mondshein, three-time national AAU decathlon champion and 1948 Olympian. In their first head-to-head meeting, Kremser almost equaled McClellon, leaping 6-7 for second, another PR. With the German vs. the African-American youngster matching jumps in friendship, the competition was reminiscent of the Jesse Owens-Lutz Long engagement, under the Fuhrer’s disapproving gaze, in the 1936 Olympic long jump at Berlin. *Jan. 25, St. Francis Prep Games at the Armory: Jumped 6’ 5 ¼” to tie for first with five other jumpers including Kremser. *Feb. 2, Mayor’s Meet at the Armory: Jumped 6-3.50, first place. *Feb. 16, NYU Meet at the Armory: Jumped 6-7.50 to defeat Del Benjamin. *Feb. 22, AAU National Scholastics at the Garden: Jumped 6-7 to tie for first with Carl Dawkins, a junior from Somerville, Mass. *Feb. 29, PSAL City Champs at the Armory: Jumped 6-8 for national high school indoor record to complete the winter season. (Flawless jumps from 5-10 to 6-7, made 6-8 on second attempt, missed three times at 6-9). Outdoors, McClellon’s 1964 best was 6-8.50, a national outdoor soph record, earning him his first international trip, that June, to compete at White City Stadium in London against the British. Traveling with the New York Pioneer Club, and representing the United States, McClellon, still 16, won his event with 6-8. It was McClellon’s first plane trip, first hotel room, first everything. “What impressed me most,” recalled McClellon, “was the British accent.” The American team was a strange brew of some 15 to 20 men, including discus champion Al Oerter, who by then had two of his four straight Olympic golds in the bag; New York area high school sprint dynamo Oliver Hunter of New Rochelle; and the future University of Arkansas Hall of Fame men’s coach John McDonnell, before he ever coached, and was putting in a semester as a journeyman miler at Emporia State in Kansas. Taking the measure of the historic season for high school athletes, Track & Field News raved, if Gerry Lindgren was “unbelievable,” then Bill McClellon was “at least amazing.” # Thursday: Part 2 - From New York To San Diego, Bill McClellon Jumps Up, Up and Away Marc Bloom’s personal reflections on track and field history appear periodically. His last story can be found here. Marc’s latest book, “Amazing Racers: The Story of America’s Greatest Running Team and its Revolutionary Coach,” about the Fayetteville-Manlius cross-country dynasty, was named 2020 Book of the Year by the Track & Field Writers of America. More news |

The track arena was then called 102nd Engineers Armory. The facility was constructed in 1909 to house the New York State Military’s 22nd Regiment. Later, the regiment became the 102nd Engineering Battalion, which in turn became part of the National Guard. The unit conducted drills on the Armory floor. The main entranceway showed off military artifacts, weaponry, classic uniforms and the occasional tank — yes, a military-grade tank.

The track arena was then called 102nd Engineers Armory. The facility was constructed in 1909 to house the New York State Military’s 22nd Regiment. Later, the regiment became the 102nd Engineering Battalion, which in turn became part of the National Guard. The unit conducted drills on the Armory floor. The main entranceway showed off military artifacts, weaponry, classic uniforms and the occasional tank — yes, a military-grade tank.

“I was never intimidated,” he said.

“I was never intimidated,” he said.