Folders |

Off The Top Rope: WWE's Search For Talent Includes College Track And Field AthletesPublished by

Off the Top Rope!Collegiate stars making a leap from the track to turnbuckle

A DyeStat story by Dave Devine Images courtesy WWE or social media accounts __________ In an otherwise empty wrestling ring, Anna Keefer lay prone on the mat, staring at the ceiling. It might have been tempting to pause there, under the glare of the house lights. Take a beat, ponder the improbability of her situation. But Keefer had no time to reflect. No time to appreciate this fleeting stillness in an otherwise chaotic day. Not even a moment to consider, yet again, what on earth she was doing here. Here in this wrestling ring. In Nashville, Tennessee. Auditioning to become a professional wrestler. Because any second now, a whistle would sound, and Keefer would need to be up and moving again. Which, unlike body slams and piledrivers, was something she was actually good at — moving. Quickly.

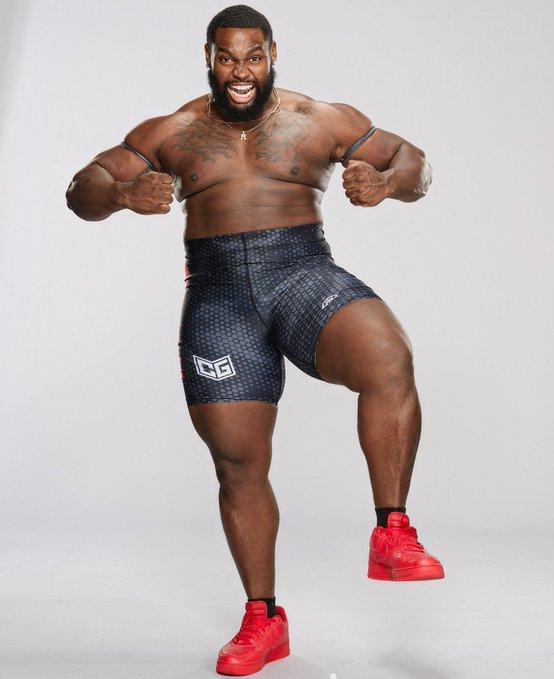

And now, near the end of the second day, she’d advanced to the final round of an assessment called the “In-Ring Shuttle Run.” It was a fairly rudimentary test for an aspiring wrestler: Begin flat on your back in the ring, spring up at the chirp of a whistle, sprint across the ring and hit the far rope, propel off the rope, barrel across to the opposite side, rebound again off the ropes, and then cross the finish line for a recorded time. The field of 50 had been narrowed to five finalists: Keefer and four male recruits. She was the last to go. The time to beat: 5 seconds. While much of the preceding 48 hours had felt perplexingly foreign to this lifelong track athlete, this part of it — competing against the boys — was something she’d been doing her entire life. Whether in fourth grade gym class or middle school recess, whenever there was a chance to race, Keefer lined up and took on all comers. In the Minnesota cul-de-sac where she grew up, neighborhood kids would congregate in one backyard or another for pick-up football; Anna never worried about waiting to be chosen when the teams were divided. “I was always one of the first picked,” she recalls, “even among the boys, because I was so fast.” So, this WWE challenge? Five seconds to leap up and criss-cross the ring? She was ready for it. Even if she wasn’t entirely sure how she’d gotten here. Or whether she actually wanted to be a professional wrestler. Or, truly, what the profession entailed. But this — leaping and sprinting — this, Anna Keefer could do. “I was like, ‘This is my thing right here. I’ve got to nail this.’” Star Search For generations, professional wrestling’s approach to talent identification was steeped in tradition, moored to a collection of mostly independent, regional promotions that would eventually nudge — or lose — emerging talent to larger, more national outfits. Without a formal pipeline, a mix of aspiring journeymen, former high school or collegiate athletes, and independent wrestlers tended to advance through the regional system based on connections and introductions, acquiring the tricks of the trade at training stables attached to prominent wrestling families — names like the Harts, the Ortons, and the Flairs — or via “wrestling schools” opened by retired or semi-retired professional wrestlers. But as pro wrestling gradually aspired to reach a broader audience as “sports entertainment,” and World Wrestling Entertainment (previously the World Wrestling Federation, or WWF) emerged as the juggernaut of that movement, it became clear that an overhaul was needed in the approach to talent recruitment. Enter Paul “Triple H” Levesque. A 14-time WWE Heavyweight Champion and Hall of Fame inductee, Levesque is currently WWE’s Chief Content Officer, overseeing all creative efforts and talent development for the company. Although his own wrestling path hewed closely to the traditional model — former prep baseball and basketball player turned bodybuilder who landed, via a series of introductions, in a wrestling school run by a retired pro named Killer Kowalski — Levesque quickly grasped the need for a new model after making the transition from the ring to the boardroom. His efforts, over the last decade, have borne fruit in two distinct ways. In 2013, WWE opened a $2.5 million, state-of-the-art Performance Center in Orlando, Florida. At more than 25,000 square feet, the training complex features an open auditorium space with seven wrestling rings, a broadcast booth, a studio where wrestlers rehearse television promos, along with locker rooms, weight rooms and sports medicine treatment on par with elite Division 1 collegiate programs. Which dovetails nicely with Levesque’s other primary initiative. In recent years, WWE has shifted its focus from courting emerging regional wrestlers to recruiting prospects directly from the college ranks. And that effort is centered, not merely on the expected sports like wrestling or football, but on student-athletes from across the spectrum of NCAA offerings. Basketball. Lacrosse. Cheer. Gymnastics. Tennis. Softball. Soccer. And notably, based on the number of athletes currently advancing into the WWE fold — Track and Field. The raw athleticism of track athletes, the foundational attributes like speed, strength, explosiveness and agility — even in the absence of more refined grappling skills — make them an attractive draw for WWE recruiters. Indeed, WWE’s current Raw women’s champion, Bianca Belair (pictured above) is a former collegiate track athlete. An All-American hurdler at the University of Tennessee under the name Bianca Crawford, Belair is arguably the most famous female wrestler on the planet. She was also an early beneficiary of the Performance Center, apprenticing there in 2016, but even Belair followed a more traditional route to the WWE, entering the ranks in her mid-20s after stints in fitness modeling and CrossFit competition. With the new, Triple H-championed approach to talent identification, the WWE imagines careers that begin earlier than Belair’s, and extend longer. A cadre of carefully selected “Superstars” with a range of athletic preparations and backgrounds. Think: social media savvy, crossover audiences, more diversity and greater gender equity. And training that begins, for many, immediately after college.

True Calling When Rickssen Opont received the direct message on his Instagram account, he wasn’t sure whether to believe it or not. A former conference champion shot putter at the University of South Alabama (after four years at Division 2 St. Thomas Aquinas), Opont was training as a post-collegian in Mobile when the DM arrived, inviting him to attend a WWE tryout in Tennessee. He remembers thinking: “Hold up, this seems like an amazing opportunity. I really hope it’s not a scam or a joke.” But it was neither. After confirming the validity of the Instagram account that sent the invite, Opont responded and was on a Zoom call with WWE representatives the next day. It was, he says, the opportunity he’d be waiting for. Born in Haiti, Opont lived there until he was 9 years old, and then moved to New York to live with his father and stepmother. For a shy boy who spoke little English, it was a difficult transition to the United States. “I had to learn a whole different language,” he says, “adapt to a different culture and environment. It was very overwhelming and tough.” He faced frequent bullying from classmates in New York, suffered crushing self-doubt for years. Only when he discovered weight lifting, and then found track and field’s throwing events in high school, did Opont discover a way to build confidence and positivity alongside muscle. “The person I am today is a direct representation of everything I went through,” he says. “Yes, I’m physically strong, I can lift a certain amount of weight, but at the same time, I grew up feeling broken my whole life.” Given his background, Opont now strives to be a light for others, to help — particularly young men — avoid feeling the way he did growing up. Part of that effort is an initiative he’s developed and promoted on social media for several years: Chasingr8ness. It’s a branding effort that Opont is fairly certain, along with this throwing prowess, caught the attention of WWE recruiters. Ironically, Opont grew up with only a vague awareness of professional wrestling. His, as he says, “strict Haitian parents” forbade him from watching matches on television, due to the violence. “I might catch it here or there,” he allows, enough to pick up names like The Rock or John Cena, “but it was definitely not something my parents allowed me to watch.” Nevertheless, when that WWE message landed — Join us at the Nashville tryout on the weekend of SummerSlam 2022 — it cracked open a future Opont hadn’t known he was seeking. “The moment I got that message,” he says, “it clicked. That was what I was meant to do, and I started training for it.” But he wasn’t the only one perplexed by the WWE invitation. Keefer, the UNC long jumper and sprinter, received a similar DM in the spring of her final track season and found it equally confounding. “It was a little bit bizarre,” she says. “Being a track and field athlete and receiving a message from the WWE, I’m thinking, ‘This can’t be right.’” Keefer grew up in an athletic family. Her mom, Tiffini (Kramer), was a heptathlete at South Dakota State, where she still holds the school's long jump record. Her younger brother, Max, is currently on the track and field team there. Her dad, Tim, and two uncles played college football. One of them wrestled. And Keefer’s grandmother, at a time when athletic options were limited for women, was a state badminton champion. But none of them were professional wrestlers. Keefer wasn’t sure she wanted to be one, either. Her post-graduation plans were set on continuing a career in track and field, although she was unsure of exactly how to go about doing that. She realized, at a minimum, it would be a financial stretch: training independently, affording gear and traveling to competitions without any formal sponsorship. “It wasn’t the most realistic idea,” she says. Still, she approached the WWE tryout lightly, more like a bucket list item than a future career option. Something cool to do in the summer, before she got on with the rest of her life. Opont had a different take. He suddenly felt like there was a great deal riding on his impending tryout. He expanded his cardio workouts, continued the heavy lifting he’d been doing, dug deeper into some gymnastics and tumbling work he’d already been attempting. Although, he had competed internationally for his native Haiti, holding national records in the shot put and hammer, he quickly grasped that wrestling might offer greater stability than the uncertain Olympic dreams he harbored. At the Nashville tryout, he was the guy hyping up fellow recruits as they moved through the paces. The one who cheered each competitor. The dude who excelled when the mic was in his hand. “I didn’t do those things to get signed,” he clarifies. “That’s who I am naturally. It was an opportunity where I finally — finally — got to shine for being myself. The moment I stepped in that ring for the tryout, I knew this was what I was meant to do.” Although Keefer was less certain about her future in the ring, her confidence grew with each test she mastered. And then came the In-Ring Shuttle Run. And the top time on the board: 5 seconds. Beat that, and you’ve beaten all the boys. Just like those recess races. The backyard football. “I went 4.8,” Keefer says, laughing. “And everybody went crazy. It was kind of a cool moment.” When she left the ring, Triple H — not many call him Paul or Mr. Levesque — took her aside, shook her hand, told her how impressed he’d been. “That moment,” she says, “was pivotal in thinking I might be able to do something with this.” A day later, as the tryout concluded, a small number of competitors were told to remain behind for what was described as a “media availability.” Keefer and Opont were among those asked to stay. After a few cursory interviews, Keefer assumed they’d be boarding the bus to the hotel. Instead, she was ushered through a nondescript door into a room with a polished wooden table. “I walk in,” Keefer recalls, “and there’s these bright lights, like a studio filming me, and Triple H and a few other people are sitting at this conference table. It was like some grand scene, and I walked into the middle of it.” Invited to sit across from Triple H, she immediately noticed a manila envelope on the table with her photo attached to the outside. After a brief prelude, Levesque offered her a contract to train with WWE at the Performance Center in Orlando. “I was so shocked,” Keefer says. “I seriously thought we were getting on the bus.” After that, Opont had his turn in the conference room, too. But by the time he was called in, word had reached the remaining recruits and he already knew he would be offered a contract. That didn’t drain any of the joy or astonishment from the moment. In all, 14 of the 50 invitees were invited to Orlando. Five were former NCAA track and field athletes. Besides Keefer and Opont, the others were Louisville and Rutgers high jumper Alivia Ash; Clemson horizontal jumper Harleigh White; and Eastern Michigan thrower Chukwusom Enekwechi. “It felt like a dream,” Opont says. “The whole three days.”

NIL: Next In Line Triple H had another move up his sleeve. In July 2021, when the NCAA enacted its name, image and likeness (NIL) policy, allowing student athletes to be financially compensated for the use of their name, image or likeness while still in college, WWE was already working on a plan to merge its recruitment ambitions with the new regulations. Again, under Levesque’s leadership, the company envisioned a program to forge long-term relationships with current student-athletes, particularly those with large social media followings, in a venture to expand the WWE talent pipeline and draw new fans to the sport. Distinct from post-collegiate “tryout” events like the one that brought in Keefer and Opont, this initiative would provide a separate, direct pathway from college athletics to WWE. By December 2021, WWE unveiled their inaugural class of NIL student athletes, adding a twist to the acronym by designating their program “Next In Line.” Of the 15 athletes named to the first class, five were from NCAA track and field programs: Ohio State thrower Carlos Aviles, Wake Forest mid-distance runner Aleeya Hutchins, University of Kentucky hurdler Masai Russell, and two from the University of Alabama: thrower Isaac Odugbesan and pole vaulter Riley White. In the months since, WWE has selected two additional NIL “classes” (for a total of 46 signed), featuring prominent track and field stars like Rachel Glenn, an NCAA champion and World Championship-qualifying high jumper from South Carolina; Turner Washington, a four-time NCAA champion in the shot put and discus from Arizona State; and Alia Armstrong, the reigning NCAA 100-meter hurdles champion and World Championship fourth-place finisher from LSU. While the “Next In Line” program is, at its core, a talent recruitment pipeline for WWE, there is no requirement that enrolled athletes begin training as wrestlers after graduation. While still in school, NIL athletes receive, according to WWE’s release, “access to the WWE Performance Center, along with resources in brand building, media training, communications, live event promotion, creative writing, and community relations.” WWE knows that not every signing will pan out — at least not immediately. Some athletes will pursue professional careers in their primary sport. Others will continue training in the hopes of making an Olympic team. Still others will step away from sport entirely. But the “Next In Line” program assures signees they will receive support in pursuing those other athletic avenues first, along with encouragement to return to the wrestling stable when those ventures have concluded. The long game, of course, is that by investing in enough prodigiously-talented athletes over time, a significant number will aspire to become the next generation of WWE Superstars.

Child's Play Carlos Aviles had long dreamed of wrestling stardom. As a child growing up in Ventura, Calif., he thrilled to early-2000’s WWE headliners like The Undertaker and Shawn Michaels. But it was the high-flying, ladder-leaping daredevil, Jeff Hardy, who truly captured his imagination. On Saturday mornings, Carlos and his brother Camilo would charge from their bedroom, each wearing some cobbled-together version of Hardy’s signature arm sleeves, blasting the wrestler’s entrance song as they prepared to duplicate his moves in the living room. The Aviles brothers were big fans. But if Carlos honed any actual wrestling skills during those childhood sessions, they’re mostly gone now. He’s currently a standout thrower at Ohio State and a two-time Salvadorian national champion in the shot and discus for his mother’s homeland of El Salvador. But he also grew from that kid racing down the hallway into a 6-foot, 6-inch, 305-pound colossus, which might explain the message he received, out of the blue in July 2021, asking if he would be interested in the new NIL program that WWE was launching. Aviles actually ignored the first DM from the WWE Recruit account, noting that the page had hardly any followers. But when a second message arrived three months later from the same account, it came with more than 100,000 followers and a blue authentication check. “I thought, okay, this might be the real thing.” Acknowledging he lacks the social media following that some of his fellow NIL signees bring to the table, he figures his size and physicality caught the attention of WWE talent scouts. His explosiveness and agility, he points out, “the things I do with the shot and discus,” the way he channels that power in a small circle — all of that translates into things he might do in a wrestling ring. “A lot of things correlate,” Aviles says, “Strength is only part of it.” While many members of WWE’s first NIL class had experiences similar to Aviles — identified and contacted over social media, in sometimes confusing ways — by the time the second cohort was assembled the program was better understood and more widely established. Athletes began reaching out to WWE. Rachel Glenn, one of the star recruits of the second “Next In Line” class, contacted WWE after watching her friend, Masai Russell, navigate the experience as a member of Class 1. “I was thinking, we both run track, and if Masai can do it, I can do it,” Glenn recalls. “Why not hit them up and see what opportunities there are?” WWE showed immediate interest in Glenn, an NCAA high jump champion for South Carolina who would go on to qualify for the 2022 World Athletics Championships in Eugene, Oregon. “I was trying to make moves for myself,” she says, acknowledging she knew little about the wrestling business before reaching out. “That’s the crazy thing — I had no idea what WWE was. I knew it was some kind of fighting, of a sort, but I had no knowledge of the WWE.” It was no surprise then, last April, when Glenn and other members of the first two NIL classes — including Aviles — were brought to WrestleMania 38 to experience WWE’s signature card in person, she spent most of her time trying to decipher the action and figure out who she was watching. While Aviles was greeting stars like Brock Lesnar and hoping to catch The Undertaker in the green room (he didn’t), Glenn was discreetly searching up names on her phone. “I really didn’t even know who they were,” she says. “I was sitting in a chair Googling everybody. I was also like, ‘Why are they all being so dramatic?’ This is literally my whole first experience with WWE.” But if the drama in the ring was unexpected, it also opened an avenue for Glenn to connect more directly with this newfound wrestling scene. Because back when Aviles and his brother were practicing ring entrances, Glenn and her sister were acting out roles from Disney shows in their childhood home — with a similar attention to costumes and music. Later, Glenn would take three years of drama in high school, although track commitments would keep her from performing in any of Long Beach Wilson’s theater productions. “When I heard that professional wrestling had an acting aspect to it, I thought, ‘Okay, I’m familiar with that part, I can get with this.’” Neither Glenn nor Aviles has visited the WWE Performance Center yet. There’s a trip planned this spring for members of all three NIL cohorts. For now, each continues with their collegiate track and field experience, both with an eye on future national team berths and Olympic Games — Glenn for the U.S., and Aviles for El Salvador. Any future role in a wrestling ring is at least a year or two away. But hardly a day passes without a family member, friend, or even casual acquaintance peppering them with questions. What’s your wrestling name going to be? Do you think you’ll be a good guy or a bad guy (or, in wrestling parlance, a “babyface” or a “heel”)? Aviles has given this plenty of thought. “I think I want to dabble in the villain space a little bit — you know? I want to have that nasty, dirty mojo type of thing. Being so large, and having a big head of hair, I could do some damage when it comes to the villain space.” Glenn has a similar response, but for a different reason. Years ago, when she and her sister were acting out those Disney shows, Rachel tended to gravitate toward a certain role. “I’d always be like, ‘I’ll be the mean girl,’” Glenn says, “So, I feel like I would be a villain. I can do a real good job with a villain.” She’s less certain about her ring name. “My friends always ask me that, but I’m not sure what goes well with Rachel. People have said, ‘Rowdy Rachel,’ or “Rascal Rachel’ — but maybe I’ll change my whole name or something. It’s a work in progress.”

New Language Anna Keefer is still a work in progress She wakes up achy most mornings, examining random bumps and bruises in the mirror. Running a finger across a mat-burn on her shoulder blade. Poking at a welt the length of her thigh from a ring rope. A goose egg on her forehead from a poorly-executed headbutt. “It’s something that, unfortunately, you have to get used to,” she says. “Your body adapts in some ways, but in others, you just get beat up.” She’s been at the Performance Center in Orlando for several months now, trying to perfect this craft. Attempting to make the transition from track and field athlete to professional wrestler. Rickssen Opont, the thrower from South Alabama, is there, too. Along with the other successful members of the SummerSlam tryout and several members of WWE’s first NIL class. Most of them live near one another in an apartment complex close to the training facility. All are full-time, professional athletes under contract with WWE. Their days are busy with in-ring lessons, strength and conditioning, promo classes, and travel to weekend events and community outreach obligations. For Opont, much of the discipline that made him a successful thrower and student-athlete has transferred to his ringwork in Orlando. The training intensity, the mental preparation, the thousands of repetitions, over and over — it all translates. “It’s the same blueprint going into this,” he says. “Learning how to do something new. It’s all about getting reps, and not being afraid to make mistakes.” Keefer has seen a similar carryover from track to wrestling, but she misses the pure objectivity of her events on the oval. How the time on the clock or the hashmark on the measuring tape tangibly defined her success. “Now,” she says, “I have a whole day of practice, and I’m like, ‘Well, I hope I did okay.’ I’m 24 (years old) and I’m trying to learn something brand new.” She struggles, more than she’d like, to carry the same confidence she held on the track — or even during the WWE tryout — into the Performance Center practices. She’s still adapting to the choreography of grappling with an opponent. “It’s like learning a new language, honestly,” Keefer says. “I’ll pick up a few sentences and feel good some days, and then all of the sudden I hit a plateau. It just takes a long time to get good and feel smooth in the ring.” She’s had two matches so far, both untelevised — what are known as “house shows” in the business — and each went well. She still doesn’t have a ring name or a persona, but she expects future audiences will play a role in deciding whether she’s cast as a babyface or a heel. Opont hasn’t yet contested a match, but he expects to soon. With his tireless positivity and compelling personal story, he already has a sense of the wrestler he’d like to become. “I’m capable of being a heel,” he says, “but with the goals I have with Chasingr8ness and my journey in life, I feel like being a babyface is the best route for me.” He can’t help thinking back to that 9-year-old boy from Haiti, recently arrived in New York. How he struggled with the language, faced bullying as a child, felt broken and hopeless at times. How he found weight lifting, and then track and field, to elevate his confidence. And how his strict Haitian parents prohibited him from watching wrestling on television. “Crazy how life turns out,” he says. “Now I’m learning that business from the other side of the television. Just patiently waiting for my opportunities, and —” He hesitates, and somewhere in the pause is that little boy again. Or the hint of a quicksilver girl, playing backyard football. The boys in the hallway, wearing homemade arm sleeves. The sisters, giggling and dividing up Disney roles. Kids with dreams. “I’m just waiting,” he says, “for my time to shine.” More news |

Keefer was a star sprinter and an All-American long jumper from the University of North Carolina, only two months removed from her May 2022 graduation, when she traveled to Nashville for this three-day tryout at the invitation of World Wrestling Entertainment. One of 50 recent collegiate grads recruited by WWE to audition as part of SummerSlam 2022, Keefer encountered 12-hour days packed with a variety of physical and mental challenges which somehow both closely mirrored and wildly deviated from her experience as a collegiate athlete.

Keefer was a star sprinter and an All-American long jumper from the University of North Carolina, only two months removed from her May 2022 graduation, when she traveled to Nashville for this three-day tryout at the invitation of World Wrestling Entertainment. One of 50 recent collegiate grads recruited by WWE to audition as part of SummerSlam 2022, Keefer encountered 12-hour days packed with a variety of physical and mental challenges which somehow both closely mirrored and wildly deviated from her experience as a collegiate athlete.