Folders |

The Legend of Maud: Chris McKenzie and the Birth of Women's Track and Field - Part Two - By Marc BloomPublished by

Chris McKenzie Runs World Record Relay in London in ‘53, Moves to the NY in ‘55, Starts Protesting U.S. Track Officials’ Bias Against WomenHow McKenzie Found an Olympic Coach in Britain, Met Her Future American Husband, and Began to Reject U.S. Limits at the Peak of Her Running CareerSecond of Three Parts By Marc Bloom for DyeStat (Part One Summary: As a child in London, Chris and her family endure the deprivations of World War II and Chris, nurtured by a former world-class runner, Anne Stone, overcomes what doctors told her was a permanent leg ailment to start running as a teen-ager with great success.)

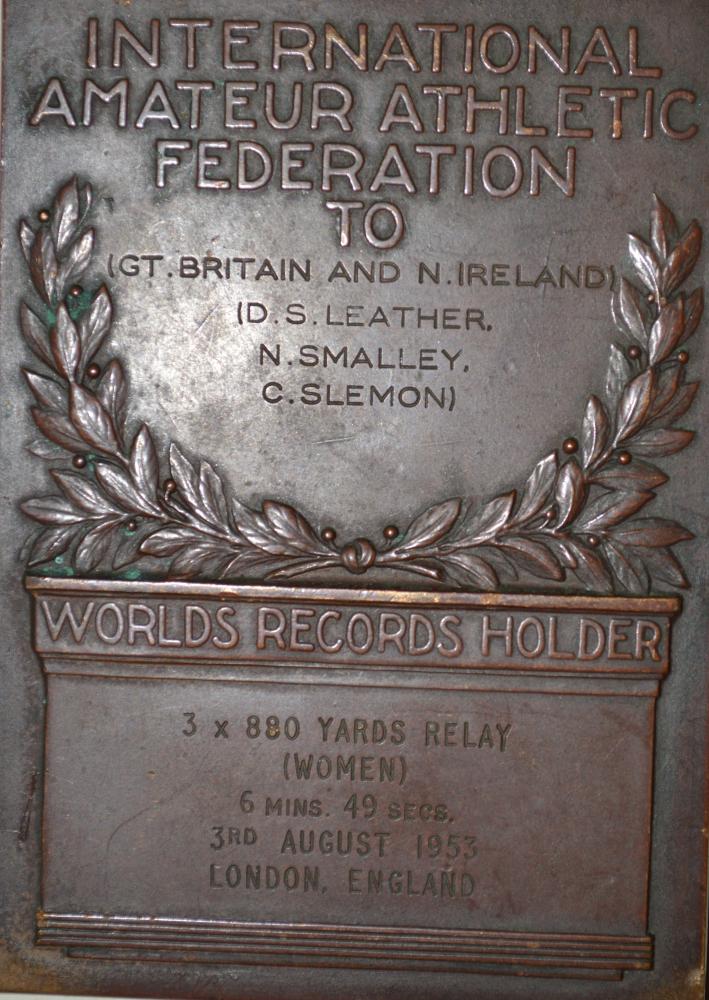

While competing for Selsonia Ladies and its coach Reg Bale in the early ‘50s in London, Chris did a mix of training, mostly distance, going as long as six miles. She was more fixed on the running experience than performance. She never forgot that 1947 cross-country race in Scotland. It was not that first victory that stayed with her as much as the seductive beauty of the wide open spaces. “I’d never run through a stream before,” she said dreamily. Chris found work as a dressmaker. It was humble work but it gave her a whiff of royalty. She and co-workers made the wedding dress for the Duchess of Kent, the title given to the wife of the Duke of Kent, a member of the Royal Family. The Duke, Edward, was a first cousin of Queen Elizabeth II, the Queen of England since 1952. Running royalty entered Chris’ track life when Arthur Wint noticed her at Battersea Park, an iconic London training site used by the greats. Wint, the first Jamaican Olympic gold medalist, in the 400 at London in 1948, was coaching along with training for the Helsinki Games of ’52 when he approached Chris, who had no idea who he was. Wint introduced himself, Chris told him she was training for the half-mile, and Wint offered to help. Chris was reluctant because of her affiliation with Bale but agreed to try Wint’s program. At the time, Chris’ 880 times were 2:35 to 2:40. Wint started her off with 5 x 440 in 75 seconds. “I felt good,” said Chris, “and after that I could go home.” A few days later, Wint gave Chris 10 x 440 in 75. She was taken aback but did them. Then, 15 reps. Chris fretted. When could she go home? Then, 20 reps. “I told him, ‘You’re crazy, I could never do 20.’” But she did the workout. Then she went home. Soon, Chris was running the 880 in close to 2:20 and British track authorities took notice. In 1953, Chris was invited to run a 3 x 880 relay, a special event at the Britain vs. France dual meet, for a crack at the women’s world record. In those days, relays with 800 or 880 legs were typically composed of three members. The meet was held at White City Stadium in London on Aug. 3. There were a number of Americans also invited to compete. One of them was a distance runner from New York, Gordon McKenzie. “I didn’t want to go to White City where they watch you,” said Chris. “People pay to see the races and would expect me to perform. I didn’t want that.” She performed alright, and so did others. Running on the British “B” team assigned to pace the “A” squad, Chris and her two relay mates won the race in world record time, 6:49.0. The “A” trio was second in 6:49.6 with France third. The official splits: Norah Smalley 2:18.5 on the lead-off, Chris McKenzie 2:16.1 running second, and Diane Leather closing with a 2:14.4 anchor. Chris received the baton with a 2-yard deficit and handed off to Leather (who would become the first woman to run a sub-5:00 mile) 3 yards ahead.

But Chris’ split time remains a bone of contention and, at the same time, figures prominently in her chance meeting with McKenzie, a tale worthy of Hollywood—Bogey and Bacall, if you will. With her gorgeous, flowing stride and radiant athletic beauty, Chris, 5‘ 3 1/2” and 100 pounds soaking wet, had star power whether she liked it or not. One U.S. newspaper account called Chris “a winsome miss with a delightful British accent.” Chris had many suitors in the track ranks. One was Britain’s Brian Hewson, second in the 800 that August day behind Roger Bannister, and a sub-4:00 miler in 1955 the year after Bannister first did it. Chris had broken off with Hewson for his attitude toward women later expressed in his 1962 memoir, “Flying Feet”: “Women should be graceful, attractive and feminine. On the track they are not. I hate to see women running near to exhaustion during a race. She loses all charm.” On the day of the relay record, Chris was engaged to another gentleman, a cricket player, and the wedding was set for December that year. Chris said that, he, too, was against female athletes. “He told me to hang up my running shoes,” she said, still smarting more than 60 years later from the man’s nerve.

Chris, in bare feet, holding her spikes, which always gave her blisters, did not know who this bold young man was. He continued, “I want you to know I’m never wrong when I time people.” “Are you an American?” Chris said firmly with a touch of sarcasm. Raising her voice she added, “Because Americans are never wrong.” That evening, at a dinner in honor of the athletes, Chris sat at a table with her coach, Arthur Wint, and the American miler Wes Santee. The occasion’s host was Lord (David) Burghley, at the time vice-president of the International Olympic Committee whose 1924 Olympic exploits were depicted in the Academy Award-winning film, “Chariots of Fire.” Burghley went on to win the 400 hurdles Olympic gold at the 1928 Amsterdam Games--the same Games remembered for its women’s 800 controversy. At the dinner, the secretary of the British Athletics Board, Jack Crump, the most powerful track official in Europe, came up to Chris and apologized, saying her split time announced at the meet was incorrect. He informed her it had been corrected to 2:10.2—precisely the time the Gordon had given her. Maybe that McKenzie wasn’t such a bad egg after all. Chris proceeded to break off her engagement to the cricket player. She soon had a new beau: the know-it-all American runner. Surely he would not insist she hang up her spikes. But what about those contradictory splits? It’s impossible to know how more than 60 years may blunt one’s memory. While Chris says she can see the entire day with cinematic clarity, and expresses no doubt about the 2:10, her 2:16 time is still on the books, according to the pre-eminent British track historians, Melvyn Watman and Peter Matthews. Watman, who told me he trained with Chris in his running days, and actually attended that very 1953 Britain-France meet, said that the splits listed for the three British women seem logical based on their 880 times in individual racing that season. No matter. Chris had found the love of her life. She and Gordon set out to change the world, one run at a time. After an intense trans-Atlantic courtship, Chris and Gordon came to America in March, 1955, and got married seven months later in a church wedding, attended by many runners, in the Bronx. Chris’ maid of honor was her PAL teammate, Louise Mead. Chris and Gordon found a small apartment in the Bronx close to McCombs Dam Park and its cinder track in the shadows of Yankee Stadium. McCombs attracted top runners from near and far, and was also the site of many early road races and the first stirrings of what would become the Running Boom of the 1970s.

Gordon, with a degree in civil engineering, got a position with the City of New York working in the office of the Bronx Borough President, one block from McCombs. For track affiliation, Chris joined the Police Athletic League, almost an exclusively black club, and Gordon did the same with the New York Pioneers. Gordon spurned the offer of the New York AC, known at the time for excluding blacks and Jews. It was only days before the McKenzies’ wedding that Rosa Parks had sparked the Civil Rights Movement by refusing to sit in the back of a Montgomery, Alabama bus. This courageous act, rallying the nation, also shined a light on the segregated track community, especially harsh when it came to black athletes traveling to meets. So before the McKenzies even began rattling the AAU, they broke an equally important barrier by helping to integrate track-and-field and road running. The McKenzies did not come by their enlightenment with progressive politics so much as the pure embrace of runners celebrating an open heart. Chris had a sprinter’s mentality: volatile, explosive, spontaneous. “At a wedding,” said her daughter Tina, “mom’s always last one on the dance floor.” And Chris did run some fine sprints, like a 57.9 South England 440 record before coming to the States. Nineteen-fifty-six was a big year for the newlyweds. It was Gordon’s first Olympics. He qualified for the Melbourne Games in the 10,000 meters, placing 18th as the top American. Earlier that season Gordon set a U.S. 6-mile record of 29:18.6. He was among the most versatile of runners, excelling from the mile to, later, the marathon.

Chris, on the other hand, was stymied. U.S. women still had no events longer than the 220. Women’s track-and-field was so backward that the ’56 women’s outdoor nationals included a baseball throw, while the indoor nationals had a basketball throw. Yet, the women’s national track chairwoman boasted of “great progress” based on performances and participation—all of 195 “girls” competed in the outdoor nationals. She called it an “awakening of public interest,” according to “American Women’s Track and Field,” an excellent, comprehensive history by Chris’ friend Louise Mead Tricard. But there was still no 400 or 800. Chris, only in the U.S. a year, found herself increasingly at a loss. With her urge to compete as great as ever, she would try and enter road races, and often get rebuffed by officials who insisted she start behind the men or run a different course. Chris became incensed that after enjoying broad freedoms in Britain she was denied opportunity in the U.S. She pressed officials for reasons: Why can’t a woman run? Why can’t I run? She could beat many of the men. “I just loved running,” she said simply, as though that explained it all. In a way it did. Frustrated and fed up, her rebellious streak was tapped at just the right time by a friend, Delores Dwyer, a 1952 Olympic sprinter living in Queens. Chris recalled, “One day Delores said to me, ‘I know you’ve been running in men’s races. I have an idea.’” When Delores divulged her plan, something no American woman had ever done, something unimaginable by a young female in 1956, Chris was all for it. The plan could backfire and make things worse. But it was now or never. # Coming Thursday, Part Three Photo Captions (Photos courtesy of McKenzie Family Collection)Field Day (Top): In the mid-‘50s after moving to the U.S., Chris McKenzie trains at McCombs Dam Park in the Bronx. Chris and new husband Gordon, an American star, lived in a nearby apartment. The site was used by many New York area runners for workouts and meets. World Record (second): The day, Aug. 3, 1953, when Chris combines with British teammates Diane Leather (center) and Norah Smalley (right) to set a women’s world record in the 3 x 880 yards at White City Stadium in London. Chris ran the second leg. Heavy Medal (third): The original medal awarded to Chris and her teammates by the IAAF in 1953 for setting a world record in the 3 x 880. In those times it was common for relays to have three members. While Chris’ announced split was 2:16, she says officials later corrected it to 2:10. Urban Legends (fourth): Chris and Gordon on the Bronx roads in the late ‘50s. While Gordon, an NYU graduate, trained for the Olympics, he also worked full-time as an engineer for the City of New York. Chris, meanwhile, devised methods to win greater women’s rights from the AAU. Loving Couple (bottom): Chris embraces Gordon after he sets an American record for 6 miles in 1956 in New York. Later that year, Gordon made the Olympic team for Melbourne in the 10,000. Gordon ran for the New York Pioneers and Chris represented the Police Athletic League, helping to integrate both teams.

Marc Bloom has received more than 20 journalism and lifetime achievement awards for his writing about track and field, cross-country and road running in a career spanning more than 50 years. He currently volunteers as an assistant cross-country coach at Princeton High School in New Jersey. More news

1 comment(s)

|