Folders |

Backstage With Untold Cross Country History: Bill Leahy And Van Cortlandt Park's First Sub-13Published by

Van Cortlandt Park’s First Sub-13:00The Run For All TimesBy Marc Bloom It happened with barely a whisper. There was no media presence that fall day at Van Cortlandt Park. No meet announcer crying out with the news. No interviews, no photos, at least not that anyone could put his hands on. No footage, to be sure. No T-shirt concession. No awards ceremony. No team tents, post-race picnics or parents grabbing their kids for selfies, or, rather, Polaroids. Just a lot of sweat and the sense, then, after a high school breakthrough that could not have been predicted— not on training of 20 miles a week — that a long-awaited college scholarship offer for the young man of the hour finally was attainable. There was the hallowed course, 2.5 miles, a string at the finish — the finish close to the woods, not the current one along Broadway — and probably a time clock. It was cross country without fanfare, how cross country was originally intended to be, and perhaps how it best represented itself: as running’s soul, with the simplicity of arduous effort over natural terrain, and pleas for mercy when tender bodies built of fire come flying down the home straight with all they’ve got. It was a small meet with a handful of schools, some from New York and some from out of town. One in particular from Boston: Catholic Memorial, a fairly new school in the Irish Catholic West Roxbury section of the city. It was a working class community. The Catholic Church commanded respect and adherence. If a bunch of street-corner kids were playing poker after school, a priest taking notice would stop and sneer and admonish the lot of them with the warning, “If it wasn’t for your parents, you’d all be in Walpole,” referring to the state prison an hour away. Even the whispers of what had occurred that day in the Bronx — Nov. 11, 1963, Veteran’s Day, a Monday —were short-lived. Soon, new stars like Marty Liquori and Denis Fikes would emerge on the course and run much faster, subsuming the historic performance, as though it belonged to another era — one with cinder tracks, meat-and-potatoes running diets and canvas high-tops for racing shoes. At the same time, a veritable revolution was on the horizon with the likes of Jim Ryun and Gerry Lindgren upending every teen-age standard and worldview of what was possible. They were soon followed by Steve Prefontaine and Craig Virgin and Alberto Salazar; and with Bill Bowerman and others exploring the new jogging trend and devising ways to run faster and longer with knowledge of physiology and biomechanics, who the heck was going to remember what a kid named William J. Leahy, Jr., of Catholic Memorial ran for two-and-a-half miles at Vannie on a fall Monday in 1963? I would. I would remember Bill Leahy because, for one thing, I competed myself the very same day at Van Cortlandt, one of many particulars I recently learned that Bill and I have had in common in the last 59 years.

In my diary’s summary, I listed Leahy’s breakthrough along with my team’s highlights, as though I somehow took ownership of Leahy’s race — not surprising because before long I would be covering Van Cortlandt meets for The New York Times and Long Island Press and establishing the first high school all-time performers’ lists for the 2.5-mile course. My Sheepshead team notations included a new school record of 14:10 (the guy who set it went on to run the Boston Marathon), and the audacious claim — remember, I was 16 — that this was “the best team in SBHS history.” Quite a distinction since the school had opened four years before in 1959. Leahy’s Catholic Memorial had opened in 1958, as an upstart rival to Boston College High, almost 100 years old at the time, for those seeking a Catholic education. Eventually, the greatest athlete ever at Sheepshead, and one of the best ever to come out of the whole of New York City, would land right there in the heart of Boston. Rico Petrocelli, Sheepshead ’61, was first team All-City in basketball (Michael Jordan, trust me, had nothing on this guy), and even more renowned in baseball, named the No. 1 player in New York, earning a contract with the Boston Red Sox. After a stint in the minors, Petrocelli made his major league debut at Fenway Park in September, 1963, barely two months before Leahy’s run, and would become an all-star shortstop. Just as I would never forget the Friday Night Lights heroics by the 6-foot Rico alley-ooping through frustrated opposition in our packed gym, soon I would also never forget the name, Bill Leahy. I left the park that day relieved that my fall season was done, flush with our team victory and anxious to pick up a hero sandwich at a deli up on Broadway for my post-race feast on the two-hour subway ride home. Bill Leahy? Never heard of him! Not until the next day’s New York Times, Tuesday, Nov. 12, 1963, with the sports section headline: “Leahy Sets Harriers Record In Retaining Schoolboy Title” The three-paragraph story had the goods, but don’t assume The Times sent a sports writer up to Van Cortlandt. For the IC4A, maybe; but not a small meet with no particular pedigree. The story carried no byline, and I’m pretty sure someone from the meet — the organizing coach? — phoned it in. That was typical then. Editors “on the desk” worked the phones. The story reported that Leahy, a 17-year-old senior at Catholic Memorial, had set a course record of 12:58.6. No specific mention was made of being the first to break 13 minutes — at the time something like the 4-minute mile in Van Cortlandt cross country annals. But the breakthrough, while not ballyhooed, was obvious, as the story cited the former record of 13:01.6 set the previous year by James McDermott of Archbishop Molloy in Queens. If you needed any more evidence that the story was a “phone job” — typically error-prone — McDermott was spelled “McDermitt,” and the meet, the Irish Christian Brothers Championship, was referred to as, “The Christian Brothers of Ireland High School Championship.” (Teams came over from Dublin?) The story also contained some brief “agate,” sports writer argot for meet results set in tiny, six-point type. Only the top ten were listed. Greg Ryan of Essex Catholic of Newark was second, in 13:21, followed by Leahy’s teammate, Jack Deary, in 13:25. Essex, taking five of the top nine places, captured team honors with 31 points. Catholic was second with 51. Leahy’s margin of victory, 22.4 seconds — more than 100 yards — was mighty good over some estimable opposition. I remember reading that Times clip, but even though I had started following the top runners, with my entrée into track journalism soon to come, Leahy would become a mystery to me. As I fashioned my first Van Cortlandt all-time list in the ensuing years, I would attain intimate familiarity with the names: watching the boys run, starting to do interviews, writing them up — the “family” of elites I was helping to put on the map as distance running gained popularity with cross country as a by-product. This was especially true with Liquori, from Essex Catholic, who ran 12:23.2 just three years later, in 1966 (in the same season Dave Pottetti of Fox Lane in Westchester ran the first sub-12:30, 12:27.0), and would become the third high school sub-four miler in the next track season. The year after Leahy’s breakthrough, in 1964, his record was snapped three times, twice by Pete Randall of Stony Brook of Long Island (12:52.8 and 12:36.5) and, between those two marks, 12:42.2 by Tom Donnelly of La Salle in Philadelphia, who went on to become a Hall of Fame coach at NCAA Division III Haverford in Pennsylvania, recently retired. With records falling left and right, and further time breakthroughs, it was easy to see how Leahy’s mark would recede into the dustbin of history. But even with times tumbling toward 12 minutes and the course record proudly standing at 11:55.4, courtesy of Edward Cheserek, in 2011 (Liquori is now the 48th top performer; the 100th best runner stands at 12:28.0), Leahy’s name always called out to me as a pure and precious artifact: he started it all. But who was this guy? It is remarkable that all through the years, Leahy’s run has been the standard by which all other Van Cortlandt runners are judged. Sub-13. It’s in every conversation: the goal of breaking 13, who broke 13, how many did it, and, in the recent period, which top schools did it in team average. However, I’ve never been party to a conversation in which anyone wondered, “What about that runner from Boston who was the first?”

Other than the Liquori and Pottetti marks, only one other top-100 time from the ‘60s has survived: Fikes’ 12:25.7 from 1969. Fikes went on to star at Penn and become a 3:55 miler. But two sustaining times from the early ‘70s are worth noting: 12:22.5 by Salazar in 1975 and 12:24.5 by Matt Centrowitz in 1972; they were soon teammates at the University of Oregon. Clearly, success at Van Cortlandt signified future prominence. Five years after his Bronx run, Salazar won the first of his three New York City Marathons. Four years hence from his, Centrowitz ran the 1,500 meters at the Montreal Olympics. And notice how uncannily close the times are among the four future stars — Liquori, Fikes, Salazar and Centrowitz — separated by a mere 3.5 seconds. There’s something mystical about that. Indeed, amid track talk about the greats and their world-wide notoriety, you will still find those long in the tooth who demand, “But what did they run at Van Cortlandt?” Today, sub-13 is still pretty darn good, coveted from far and wide, just as it was in 1963, when Peter Farrell, a Molloy senior, read the same Times clip as I did, and was stunned that Leahy was the one who achieved it. “Everyone was trying to do it,” Farrell, former Princeton University women’s cross-country and distance coach, retired, recalled when I brought it up with him recently. “It was the sacred-ness of it.” Farrell took it somewhat personally that the relative unknown (at least in New York) Leahy was the one who snared the sub-13 that had eluded his former Molloy teammate McDermott, who that ’63 season had started his freshman year at Georgetown. It was McDermott, after all, who had set a national indoor 2-mile record of 9:23.5 the previous winter at Madison Square Garden. The meet was the AAU high school nationals, held in the afternoon prior to that evening’s AAU championships for a period of years. Leahy had also run that day, a badly beaten fifth in the mile, taken aback by the spectators’ cigarette smoke choking the air. I can attest to that. McDermott’s run at the Garden carries more than a little history with it. His 9:23.5 was the last national 2-mile record B.L. — before Lindgren. McDermott may have run 9:23 on 25 miles a week. A year later, Lindgren ran 8:40 on something like 200 miles per week. In those days when everyone else barely tasted what distance meant, Molloy, coached by Frank Rienzo (who later coached Georgetown), was the area’s premier “distance” school even though the Stanners’ fall training was something out of Igloi, watered down. “We were on the track four days a week,” Farrell told me. “Our long run was a half-hour.” Given what Leahy and so many others did, that kind of schedule was par for the course, pun intended. On that training diet, Farrell himself ran 13:24 at Van Cortlandt. But for Molloy that mix was ideally brewed for a succession of national records in the two-mile relay. The next winter, in ’64, Molloy ran an indoor record of 7:49.2; in the spring, Molloy set the outdoor mark of 7:43.8. Farrell ran on both foursomes and went on to compete at Notre Dame, where, on the first day of freshman practice he took the opportunity to mock a teammate he’d heard about: Bill Leahy. It’s a good thing that Leahy grew up in a tough neighborhood because he had to swat away insults. Arriving at Van Cortlandt as a freshman for the 1960 Irish Christian Brothers meet, he said the Power Memorial boys welcomed the Catholic boys with the greeting, “Oh, you’re the punks from Boston.” Leahy delivered, let’s say, an authentic Dorchester response. And after the sub-13, Catholic’s in-house publication, Club & Sports News, boasted of Leahy’s accomplishment in its November ’63 issue, calling him, “The first schoolboy to break the 13-second mark in the history of the course.” Now that’s fast! When I set about tracking down William J. Leahy, Jr. through Catholic’s current coach, I found him, at 76, living in Needham, Mass., about 20 miles from where he grew up as one of eight siblings in a working class Boston family. Recently retired from a career in the law, as a much honored public defender out of Harvard Law School, Leahy recalled his early running days with wit and humility, along with a certain fascination that after switching from his first love, basketball, he managed to earn a place in running history. In speaking with Leahy, I hoped to uncover the values of a young runner who could produce such a wondrous effort that would stand the test of time. And without the all-consuming running programs of today, how did Leahy put aside other interests and family challenges to arrive at Van Cortlandt battle-tested for the opportune moment? I also felt that Leahy’s period had a broader significance. It was a time of American pre-eminence in distance running by men who were authentic working class heroes. Remember that Bob Schul and Billy Mills swept the 5,000 and 10,000 at the next year’s Tokyo Olympics. Mills overcame vicious Native American prejudice. Schul did his speed work at dawn for access to a track. And in 1963, a few months before Leahy’s breakthrough, Buddy Edelen achieved a breakthrough of his own, a marathon world record of 2:14:28 — the first sub-2:15. Edelen’s running “cap” was a soiled white handkerchief tied at four corners. Van Cortlandt Park, now 1,146 acres, opened in 1888. Athletes hungry for the wilds of cross-country started competing there in 1912. Through the decades, “everyone” ran the trails; it became a rite of passage. Even the erstwhile presidential candidate Bernie Sanders was tested. Sanders ran for Brooklyn’s James Madison High in my Kiwanis league in the late ‘50s. He clocked 14:16 at Van Cortlandt in 1958 and was later heralded in political stories searching for “color” as being one of the best of the city runners. Five years after that, the best in the city was McDermott, out of Queens. Speaking of his special day at Van Cortlandt in 1963, Leahy said innocently, “I knew nothing of the record. I’m sure I could not have told you who Jim McDermott was.” Leahy certainly would not have known who Tom Dempsey was. I didn’t either until my digging turned up a 13:01.5 at Van Cortlandt by Dempsey in 1957, discovered by New York State stat sleuth Kyle Brazeil. In a ’57 clipping Brazeil forwarded, Dempsey, a senior at Archbishop Stepinac in the Westchester County suburbs, raced to a 20-yard victory over Tom Laris of George Washington High in Manhattan at the Fordham Invitational, running 13:01.5. The two-graf item credited Dempsey with five meet records in five outings to that point. His Fordham time bettered his previous course record of 13:03.4 set two weeks earlier at the NYU high school meet. (There is no reason to doubt the veracity of the news item.) Laris went on to excel at Dartmouth, get an MBA from Stanford, and excel at every distance from the mile to the marathon. In 1968, he became an Olympian in the 10,000, placing 16th at Mexico City in 1968, in the high altitude that hurt most sea level athletes in races from 1,500 on up. From Leahy’s standpoint, it’s hardly relevant whether he broke Dempsey’s 13:01.5 or McDermott’s 13:01.6. He dipped under 13 minutes by 1.4 seconds. He could remember the motif of his race but few details, typical of Leahy, who embraced running’s big picture more than the transitory increments that would pass. “I loved cross country, loved Van Cortlandt,” Leahy said. “I had a very favorable feel for the course. The trickiest part was getting into those hills in good position. I liked that I had been successful at Van Cortlandt in the past.” In 1960, Leahy had won the Irish Christian Brothers freshman race (6:09 for 1.25 miles), and then the varsity division as a junior in ‘62, giving him two triumphs at the site as his senior race approached in the fall of ’63. Leahy’s summer training had been scattershot. He started out by almost collapsing in the heat of a July 4 20-k race, the longest he’d ever run. He worked at Catholic doing odd jobs like lawn mowing and painting, at times biking the 8-mile roundtrip from home. He played some pick-up basketball and, being a teen-ager, went with friends to “party” on Cape Cod. Training? “An occasional early morning run,” he recalled.

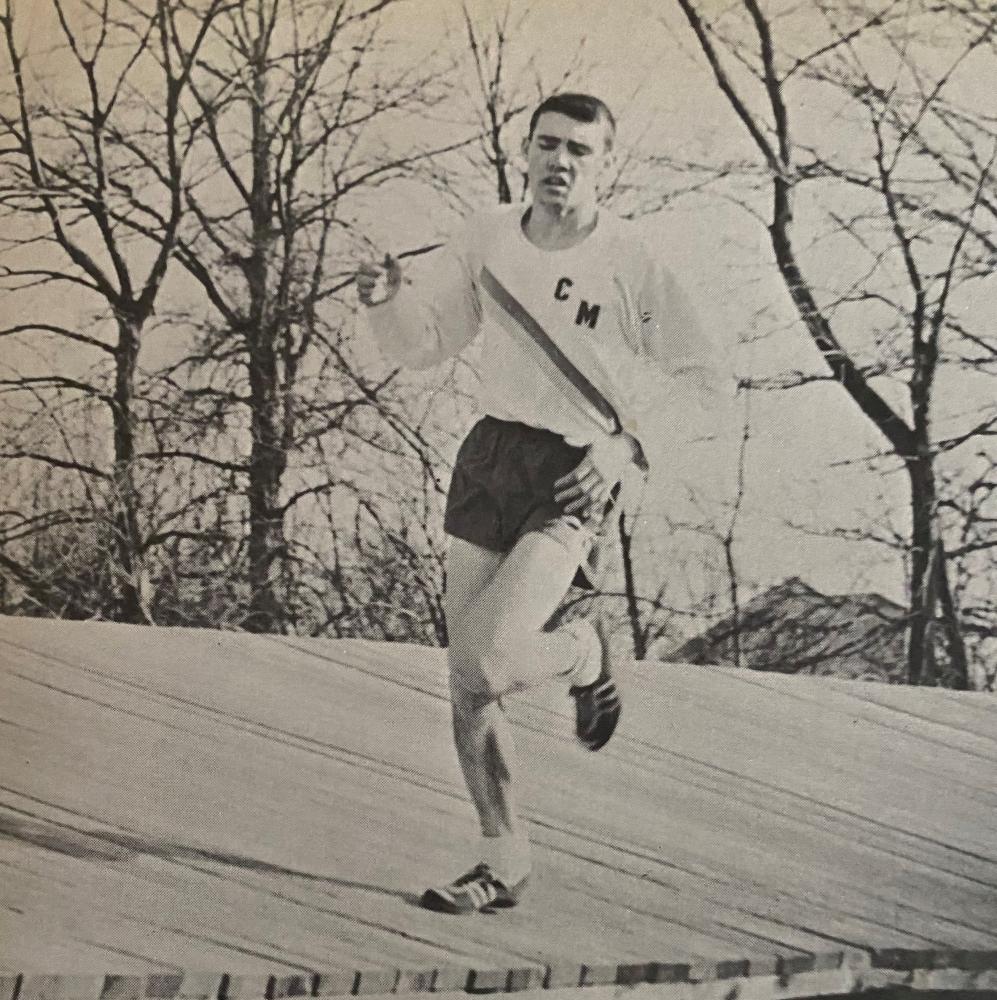

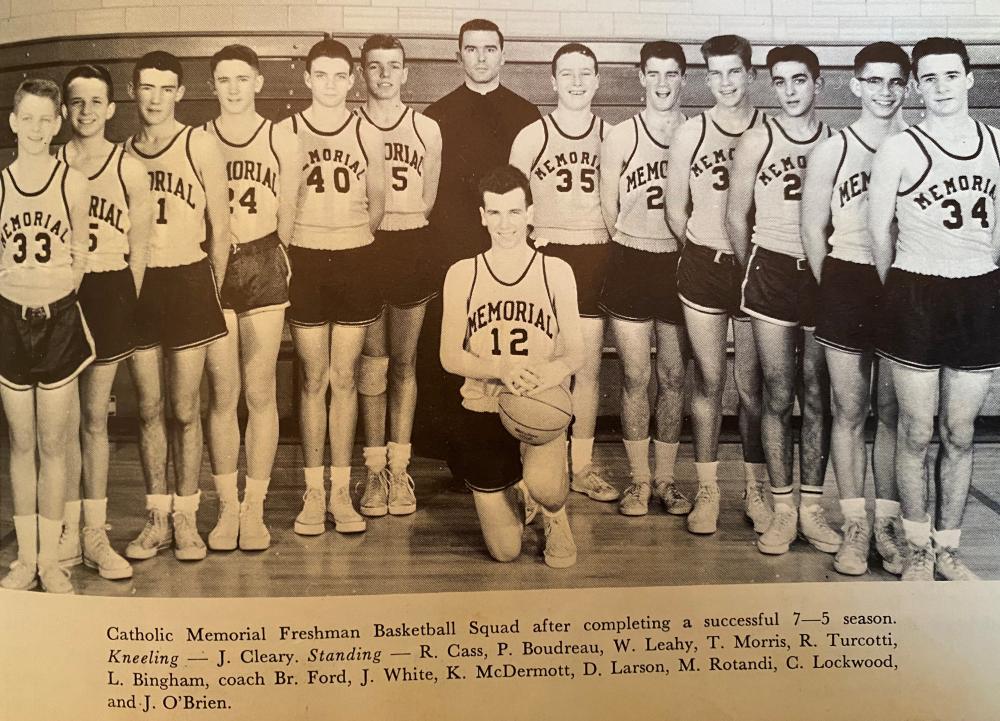

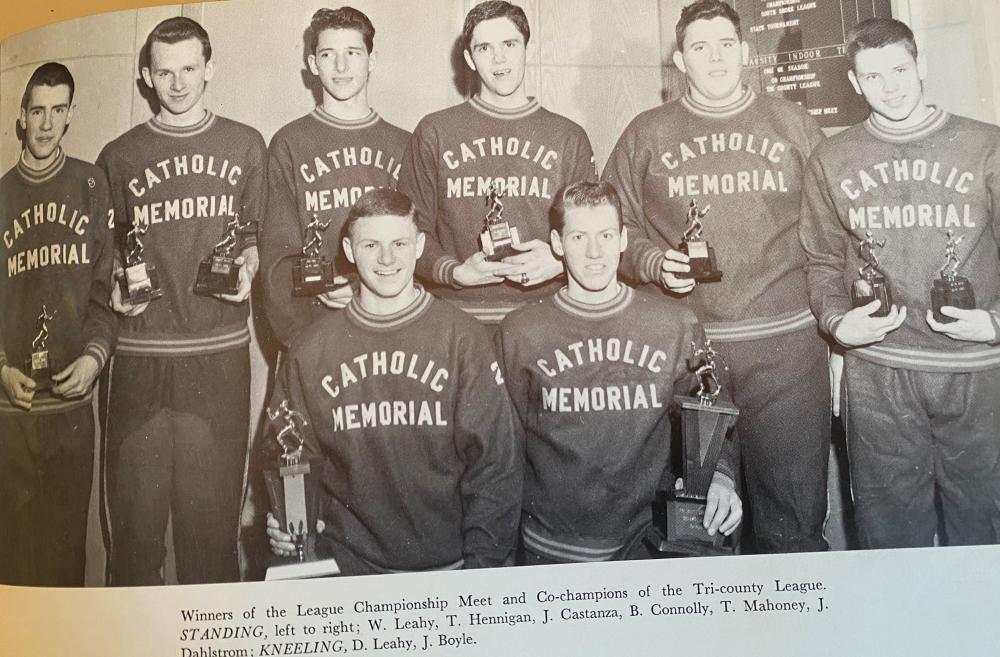

None of his friends was surprised to see Leahy still on the basketball court, the bete noire of cross country coaches. In Boston, you played basketball; and if you attended Catholic school, you played CYO, where Leahy excelled “as a ferocious, undersized” point guard. Then, Leahy was more interested in basketball than running. At Catholic, he played JV basketball as a freshman and sophomore. But in a theme that would govern his life, the track coach urged him to quit basketball in favor of track, telling the fast, athletic youngster, “Look, your family is not wealthy, in track you can get a full college scholarship.” Leahy’s father was employed by the Navy as an electrician at the Boston shipyard. His mother, with eight children to care for, was a home-maker. Leahy’s parents, children of the Depression, “devoted their whole lives,” he said, “so their children could succeed and go places they couldn’t.” Leahy blended the necessary street smarts with the nobility of a higher calling: church and an intellectual curiosity. He attended daily mass and was an altar boy. He was a voracious reader and top student. “I was fascinated by the wider world,” he said. Before high school, Leahy’s Catholic upbringing spoke to him, and he imagined himself a missionary, or even a priest, summoning the faithful in foreign lands. He saw that urgency as a marriage of the messianic with the patriotic, an outgrowth of the post-War ‘50s after barbarism was defeated and people of all inclinations were prompted to find greater meaning in life. Leahy’s mother always told him, “To those who much is given, much is expected.” Leahy recalled, “I swallowed it.” Leahy was not given much. At times, his family has trouble putting enough food on a table for 10. His father suffered a serious electrocution accident on the job. Eventually, he had to get a second job as a custodian. Leahy’s geniality as a patron of the church could find a harder edge under the right circumstances. In a CYO game, fighting for the ball, he got into a beef with the ref. They barked at each other and Leahy unloaded the F-bomb. His father, William Sr., seated close by, heard it. Just about everyone did. “I was supposed to be an icon of responsibility,” Leahy said. He had to write an apology for the parish newsletter. Then there was the time on the streets when he got into words with a kid from a rival group. The kid pulled a knife on him. Bill learned from his father not to take any crap. One morning when it was 18 degrees, the Leahys’ furnace broke. Bill’s father tracked down the company president, got him on the phone, and — telling him, “I’m the one who pays your salary” — gave him an earful. Before long, the heat was back on. Leahy looked hard at the boy with the knife and uttered, “What’s the matter, are you afraid to fight with your hands?” The kid put the knife down, a scuffle ensued and Leahy got the worst of it. While Leahy lost the battle, he won the war, at least philosophically. The street fighting man saw his destiny, as in the Rolling Stones lyric, “what’s a poor boy to do, except sing for a rock ‘n’ roll band?” Leahy had no band so he joined a cross country team. With his good grades, Leahy easily passed the entrance exam for Catholic and was awarded an academic scholarship of $250 to cover the annual tuition (which, currently, is over $25,000 per year), accepting of the one-hour trip from home in the Dorchester section. At 5 feet, 7.50 inches and 120 pounds, Leahy started track and cross country while hanging on to basketball, and it was clear from the outset where his potent mix of toughness, savvy and a higher plane of thought would be best spent. On minimal training, he won an array of freshmen cross country races and wound up 15th in the state outdoor mile in 4:39. Indoors, the team piled into a truck to go to Boston College to train on the school’s outdoor track. The Catholic kids had to shovel the lanes when it snowed. Catholic had no track of its own. By the fall of ’63, Leahy was an established runner who was setting course records in almost every meet from Boston to Providence and was the state meet class A mile record holder at 4:24.6 from the previous spring, and indoor record holder at 4:21.6, set at the old Boston Garden where the Celtics played. Leahy trained on the roads, and on wooden tracks; he liked fartlek, the changing pace. “I read where Marty Liquori was training 80 miles a week in high school,” Leahy said. “We were training 80 a month.” Leahy had a number of coaches. His primary influence was Bro. Jim Barry, a beloved school figure who started the Catholic Memorial Invitational, at Franklin Park, in 1959. On the event’s 50th anniversary in 2009, Barry, 75 at the time, told the Boston Globe, “I think a lot of them, through God’s grace — personally that’s the way I feel — they extended themselves, they became better runners, better people.”

Van Cortlandt, situated on Broadway at 242nd Street at the northern tip of a city melting pot — an amalgam of wealthy Riverdale and its private schools, working class Irish playing rugby on the park parade grounds, and orthodox Jews — was like no other course Leahy ran. He looked forward to its fast-charging opening straight, narrow funnel to the bumpy cow path, rock-strewn Back Hills, sweeping descents and final, pleading pull to the finish. There were tougher courses, but probably not trickier ones. Vannie favored the runner with sharp wits and no lapse in focus or fear. A spike wound was a badge of honor. The course was also a bit slower then, before various Parks Department cleanups smoothed the terrain, eliminated debris and added railroad ties for firmer footing. Another long-gone vestige of the course was horseback riders who would stray from the bridle path and interfere with race fields. Some 50 years ago, I wrote a feature for The New York Times in which I quoted the stable owner telling his customers to “knock the runners down.” But as I suggested in the story, the horses themselves were less of a problem than “what they left behind.” A fragile peace was eventually reached sometime in the ‘80s. With his string of course records, including one in the National Catholics at Providence College, Leahy, a few weeks out, looked like he would have the Van Cortlandt trails to himself, horse crap or not. But doubt was cast when Leahy lost twice leading up to Veteran’s Day. He placed third in the Massachusetts state meet at Boston’s Franklin Park — there was no actual state meet then so Catholic and rival schools considered the Eastern Massachusetts Champs the state finals — and then, a week later, on Saturday, Nov. 9, Leahy lost the New England title on a rainy day in Burlington, Vermont. Roger Maxfield, undefeated, from Concord High in New Hampshire, dropped his front-running style in favor of a tactical race. Trailing at the mile, he then caught Leahy, gave him a confident glance, and took off to win in 14:17 for 2.5 miles. Leahy nabbed second in 14:27. Reflecting the period’s training M.O., Concord’s go-to workout was 10 to 12 x 440 yards. Maxfield told me the team started in the low 70s with a lap recovery, and worked down to the low 60s with a 220 rest. Maxfield clocked 4:18 and 9:31 in track and went on to run for Idaho State, once racing Gerry Lindgren. He became a career military man, serving in the regular Army with a stint in Vietnam and then the National Guard, retiring as a full colonel. He lives close to where he attended high school in New Hampshire, still serving, as a town selectman. Catholic took third in team scoring. The victory went to Concord, one of the best teams in New England history, buttressed by its perfect 15-point team sweep in the state meet. That fall Concord went on to “face” Jim Ryun of Kansas in the high school nationals. Well… in those days, Track & Field News orchestrated a 5 x 2-mile “postal” (the results were mailed in) competition on the track, something of a national championship. Concord placed fifth that season. Ryun, then a junior, had the fastest individual time of all, 9:24. Two losses in a row: was Leahy’s prayed-for college scholarship out the window? The Catholic team piled into its two station wagons for the ride from Vermont to New York. It was Saturday night. For two nights they bunked on cots in the Power Memorial High School gym in Manhattan. They watched in awe as Lew Alcindor (later Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) showed up for basketball practice. On Monday, Leahy warmed up at Van Cortlandt in anger. He was angry at himself. He had something to prove. It was Leahy’s last high school cross country race. Leahy’s kid brother, Jim, a sophomore, now living in Connecticut, was the team’s pivotal fifth man. Jim knew what it meant to have one’s ego deflated. “I didn’t have a name,” Jim told me. “I was always called, “Billy’s little brother.” While Jim was also a good student, going on to Harvard Business School, and accustomed to being the family understudy, he also took pride in seeing the strength of his older brother’s personality, how Bill could maintain control while seething with desire. “Bill was the quiet assassin,” Jim said. It was a crisp and clear day. At the start, everything welled up in Bill: the church, the streets, the family’s needs; his father, who didn’t have a car at that point, somehow making it to the Bronx from Boston on his own to watch his son, as he always would. Leahy, in flats and the silver-and-red Catholic colors, wanted to leave the field behind in order to secure clean footing in the hills, where tree roots and other natural obstacles tested the nimblest of strides. “I was having a good race,” he said, thinking back to the opening mile. “I don’t remember anyone with me. I came out of the hills and over the bridge, took the steep downhill and made the left for home.” The dizzying blur of the final straight, about 600 yards, awaited him. “Somebody was yelling, “Finish strong. Go for the record!” Leahy finished strong. And he got the record, though Leahy wasn’t sure of its significance when he crossed the line. While exhausted, he stood straight, gathering in the moment, anger over. “I felt good,” he said. In our talk, he spoke of the runner’s paradox: the harder you run, the better you feel after. When Leahy got home, there were no bands playing on the streets of Dorchester. The Globe didn’t call. The church did not bestow a special sacrament. At dinner, his family still counted out fish sticks so that everyone got the same.

It was good-natured ribbing. At least that’s how Farrell remembered it 58 years later. At Notre Dame, there was a Boston-NY-Philly Catholic schools verbal “hazing.” The early workouts seemed like high school too. The first day they ran two loops, four miles, around the Notre Dame golf course. Farrell, late of his track regimen, almost puked. Leahy had a modest college career, with his best showing an 11th-place in the 1965 IC4A, back at Van Cortlandt (where he went up against his high school teammate and former state 2-mile record-holder, Deary, then running at Northeastern and finishing back in the field). But at that point, Leahy’s studies rose to prominence, with courses in theology and philosophy expanding his world view that those in need were worthy of proper embrace. Leahy felt it was his duty to serve the poor. When Leahy graduated in 1968, he was admitted to Harvard Law School. The Vietnam War was exploding and Leahy, sensing he would be drafted, applied for conscientious objector status. Not knowing whether his application would be accepted, Leahy took the Intensive Teacher Training Program at NYU, receiving a provisional teaching license and, then, a draft deferment. He found a school position in the Hunts Point section of the Bronx — again, the Bronx! New York needed teachers, and Leahy, the Irish Catholic, was given the assignment of teaching African-American and Latino studies in grades 3 to 6. In May, 1969, Leahy got married to his college sweetheart, Kathleen, from Notre Dame’s nearby sister school, St. Mary’s. He is married 53 years with three adult children, one a physician serving in the military, and three grandchildren. When a Draft Lottery, based on birthdate, was instituted in the early ‘70s, Leahy breathed relief with a high number, enabling him to leave teaching after three years without fear of draft selection. In 1972 he entered Harvard Law and graduated in 1974, cum laude. While many of his classmates went into corporate law, Leahy became a public defender, serving in numerous positions and rising high in the ranks of his field in a 47-year career. Most recently, Leahy spent 10 years in Albany as director of the New York State Office of Indigent Services, providing legal representation to 265,000 clients with a staff of hundreds of attorneys. Through the years, Leahy provided numerous services for the Massachusetts Bar and other legal aid groups, taught at Brandeis University, wrote dozens of Op-Ed pieces for lay and professional publications; and he has served on an array of advisory boards throughout the country. In addition, Leahy has received numerous judicial awards, including those from Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly, the New England Bar, New York Bar, Massachusetts Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and Juvenile Bar Association. In the courtroom, pleading for the underclass early in his career, Leahy took no prisoners, as it were, racking up not-guilty verdicts that, according to one article, “cemented his reputation as a top-gun defender.” A former rival attorney who went up against Leahy at the time called him, “smart, articulate and well-prepared, a dangerous combination.” Leahy’s moral standing was rather like that of Paul Newman’s defense attorney in the searing Irish Boston rich-vs.-poor courtroom drama, “The Verdict,” when Newman makes his passionate closing argument. “In my religion,” Newman intones, “they say, ‘Act as if you had faith; faith will be given to you.’” If all of Leahy’s gravitas — relentlessness, cunning and faith — now that’s a dangerous combination — frame the essence of the cross country runner, it should come as no surprise. From the bells of the church to the lessons of the streets to the rustle of the race course, Leahy always heard the timbre that would propel him toward something worth pursuing for its own sake — to “much that is expected,” as in his mother’s scripture. Who can say what was expected that November day in 1963? In his own way, defining the terms of history, Leahy consecrated the 2.5-mile course, letting his heart and soul provide an answer for 12 minutes 58.6 seconds. To guide him, Leahy had his own scripture, expressed some years back when he reflected on the life choices he had made. “I just gravitate toward choosing the side that’s got the uphill fight,” he said. # Marc Bloom’s personal reflections on track and field and cross-country history appear periodically. Marc’s latest book, “Amazing Racers: The Story of America’s Greatest Running Team and Its Revolutionary Coach,” about the Fayetteville-Manlius cross-country dynasty, was named 2020 Book of the Year by the Track & Field Writers of America. On Oct. 8, at the Manhattan College Invitational, Marc will be inducted into the new Van Cortlandt Park Cross Country Hall of Fame. |

Running performance certainly was not one of them. At the time, with schools were closed on Veteran’s Day, my team, Sheepshead Bay of Brooklyn, also ran our league finale, the Kiwanis Championship, that day at Van Cortlandt. A check of my original team diary from cross country ’63 shows we won the team title and I had my best time of the season. I won’t reveal my time except to say that Leahy was probably showering back in Boston when I crossed the line.

Running performance certainly was not one of them. At the time, with schools were closed on Veteran’s Day, my team, Sheepshead Bay of Brooklyn, also ran our league finale, the Kiwanis Championship, that day at Van Cortlandt. A check of my original team diary from cross country ’63 shows we won the team title and I had my best time of the season. I won’t reveal my time except to say that Leahy was probably showering back in Boston when I crossed the line. It is the prestige of an event when it can boast of a whole batch of runners nailing sub-13s on a particular day, usually one blessed with cool temperatures and dry conditions. Curious, I went to my “Harrier” cross country publication that I had put out over the years and at random picked out the Manhattan College Invitational coverage from 1998. I found that 19 boys ran sub-13, as 9,300 athletes from 313 schools in 16 states (including Wyoming) took part. The current top 100 boys performers come from 13 states including Colorado and California.

It is the prestige of an event when it can boast of a whole batch of runners nailing sub-13s on a particular day, usually one blessed with cool temperatures and dry conditions. Curious, I went to my “Harrier” cross country publication that I had put out over the years and at random picked out the Manhattan College Invitational coverage from 1998. I found that 19 boys ran sub-13, as 9,300 athletes from 313 schools in 16 states (including Wyoming) took part. The current top 100 boys performers come from 13 states including Colorado and California.

At least college coaches took notice, and before Leahy and his parents were forced to sweat it out, he was offered a full ride to Notre Dame. The Canadian Olympic medalist Alex Wilson was then the head coach. On the first day of fall practice the next year, when the Irish freshmen gathered, Peter Farrell of Archbishop Molloy told Leahy that his high school teammate James McDermott would have cleaned his clock and that the only reason Leahy set the record was because of “course erosion.”

At least college coaches took notice, and before Leahy and his parents were forced to sweat it out, he was offered a full ride to Notre Dame. The Canadian Olympic medalist Alex Wilson was then the head coach. On the first day of fall practice the next year, when the Irish freshmen gathered, Peter Farrell of Archbishop Molloy told Leahy that his high school teammate James McDermott would have cleaned his clock and that the only reason Leahy set the record was because of “course erosion.”